Chinese Dynasty: Heritage and Marvels of the Ming Dynasty

The Ming Dynasty (明朝, Míng), which reigned from 1368 to 1644, holds a significant place in Chinese history. Known for its cultural influence, stable governance, and enduring symbols like the Forbidden City and the Great Wall, the Ming era left a lasting impact on China's heritage and governance. Its achievements include architectural marvels, maritime expeditions, and literary masterpieces, making it a pivotal chapter in Chinese civilization.

Politics

Grand Secretariat

In 1380, the Hongwu Emperor (洪武帝) executed Chancellor Hu Weiyong (胡惟庸) for rebellion, abolishing the Chancellor (丞相) and Secretariat (中书省) positions. This ended the Three Departments and Six Ministries system (三省六部制) of over sixteen hundred years since the Qin (秦) and Han (汉) dynasties, consolidating power directly under the emperor. To manage state affairs, the Hongwu Emperor enlisted erudite scholars for assistance, initiating the establishment of the Grand Secretariat (内阁).

Initially a consultative body, the Grand Secretariat evolved into the highest decision-making entity. Senior Grand Secretary (首辅) sometimes wielded more power than Chancellors (丞相), with authority to propose and reject policies. However, it was never formally recognized as the central administrative body. During the Xuande Emperor's (宣德帝) reign, a system of proposal (piaoni, 票拟) and rejection (pihong, 批红) was implemented, which in fact relied on eunuchs for communication between the Grand Secretariat and the emperor, leading to the later eunuch dominance in the Ming Dynasty.

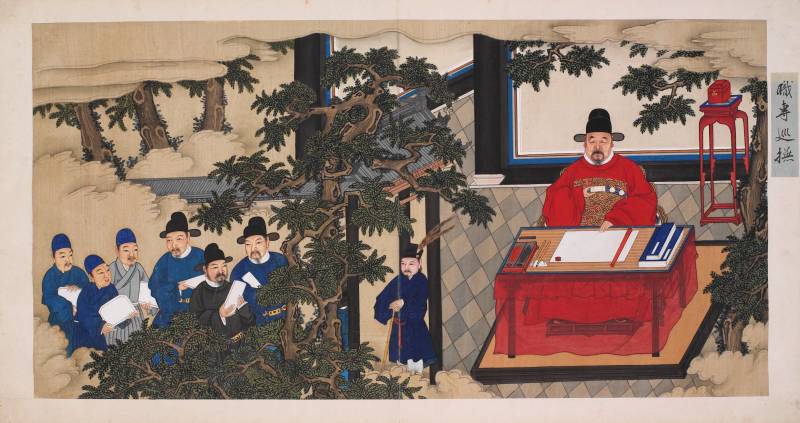

Depiction of the career of a civil servant during the Ming Dynasty: from passing the civil service examinations to reaching a high position in the government (left to right).

Secret Service

The main intelligence agencies of the Ming Dynasty were the Embroidered Uniform Guard (锦衣卫), the Eastern Depot (东厂), and the Western Depot (西厂). There was briefly an Internal Depot (内行厂) during the Zhengde Emperor's (正德帝) reign.

The Embroidered Uniform Guard collected domestic and foreign intelligence, reporting directly to the emperor and possessing the authority to arrest and interrogate individuals secretly. The Eastern Depot monitored government officials, scholars, and other political figures, reporting surveillance results to the emperor and having the power of arrest and interrogation. The Western Depot, led by Wang Zhi (汪直), was established during the Chenghua Emperor's (成化帝) reign. The Internal Depot, led by eunuch Liu Jin (刘谨), aimed to balance the power of the other agencies. After Liu Jin's execution, both the Internal and Western Depots were abolished, leaving only the Eastern Depot.

Economy

Agriculture and Handicrafts

In the middle to late Ming Dynasty, there was a shift towards specialization and commercialization in agriculture, with regions like Jiangnan (江南) and Guangdong (广东) becoming reliant on grain imports due to the cultivation of cash crops. The Yangtze Delta (长江三角洲) was prosperous in silk, cotton, and handicrafts but faced grain shortages, necessitating imports from other regions. Meanwhile, staple crops were grown widely, but population growth and the expansion of cash crop cultivation led to increased reliance on grain imports. Additionally, many landowners and gentry invested in industry and commerce, leading to the rise of prominent merchant groups.

Yunnan terraces that have been developed since the Ming Dynasty

The handicraft industry of the Ming Dynasty, particularly cotton textile production, flourished early on in regions like Jiangnan. As the capital moved north, areas like the Central Plains (中原) and North China (华北), especially around the Bohai Bay (渤海湾), also saw impressive achievements in handicrafts. Handicrafts were divided into state-owned and privately-owned sectors, with privately owned industries gradually overtaking state-owned ones in the later Ming and dominating the market. Industries such as mining and metallurgy, textiles, ceramics, shipbuilding, and papermaking progressed rapidly and were of significant scale.

Commerce

The commercial economy during the Ming saw a significant rise in status, with commercial taxes becoming a crucial source of government revenue. Wealthy merchants wielded substantial capital and often owned multiple stores, with Huizhou (徽州) merchants dominating commerce in many cities. Some merchants invested directly in production, transitioning into industrial capitalists. This rise of commercial capital contributed to regional connectivity, the growth of a commodity economy, and the early stages of capitalism in China.

However, Ming Dynasty merchants retained feudal characteristics, forming close ties with officials for business security. Urbanization rates increased, with urban populations comprising 6-7.5% of the total population by the late Ming Dynasty, reaching an estimated 15 million people by 1630.

Currency

The Ming Dynasty implemented a centralized monetary policy where all aspects of currency production and management were controlled by the court to consolidate political power. The main form of currency was the Baochao (宝钞, Great Ming Treasure Note), which was promoted throughout the country. However, this practice stopped after a few generations due to the system's ineffectiveness. Despite multiple bans, silver ingots were often used in private trade. Eventually, silver became a common form of currency, alongside copper coins, until the fall of Ming. The political and economic instability of the period also led to an unstable monetary system, and by the late Ming period, the circulation of counterfeit money (恶钱) led to severe inflation.

Science and Technology

Math, Astronomy and Mechanics

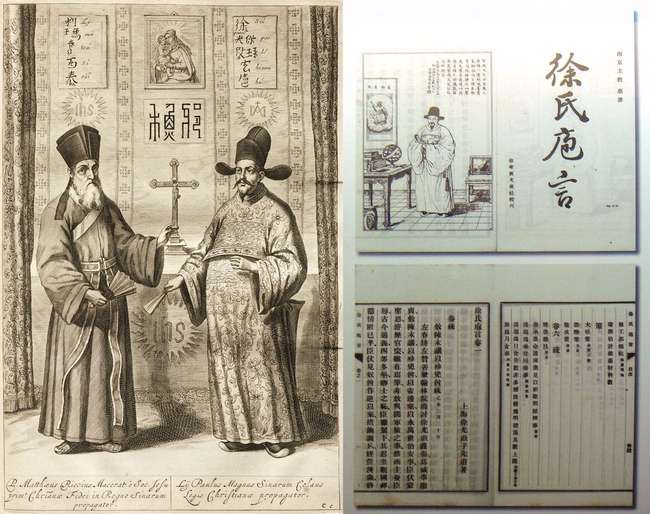

Left: Xu Guangqi (right) with Matteo Ricci (left) from Athanasius Kircher's China Illustrata, 1667.

Right: Xu Guangqi's work on military matters Mr Xu's Amateur Observations.

Scientific and technological progress during the Ming Dynasty slowed compared to the Song Dynasty. European contact spurred some advancements, such as the introduction of the telescope and heliocentric model. Although Chinese scholars like Shen Kuo (沈括, 1031-1095) and Guo Shoujing (郭守敬, 1231-1316) laid the groundwork for trigonometry, significant progress was not made until the 17th century with Xu Guangqi (徐光启) and Matteo Ricci.

The Ming calendar, despite its accuracy, lacked periodic adjustments due to institutional limitations. Attempts to reform it, including proposals by Prince Zhu Zaiyu (朱载堉), were rejected. Zhu Zaiyu also discovered equal temperament tuning.

Mechanical devices from the previous Yuan Dynasty were associated with decadence and destroyed by the Ming founder, the Hongwu Emperor. European Jesuits like Matteo Ricci and Nicolas Trigault acknowledged indigenous Chinese clockwork but noted their inferiority compared to European counterparts.

Navigation

Illustration of Zheng He's fleet

Ming China made remarkable progress in maritime exploration and navigation. The voyages of Zheng He (郑和), ordered by the Yongle Emperor (永乐帝) between 1405 and 1433, exemplify this advancement. Zheng He's expeditions reaching as far as the east coast of Africa and the Red Sea, which occurred decades before those of European explorers like Christopher Columbus, demonstrated China's advanced shipbuilding techniques, navigation methods, and maritime technology. These expeditions facilitated cultural exchanges and trade between China and other regions, including Southeast Asia, South Asia, East Africa, and the Middle East.

Agriculture

The Ming Dynasty witnessed developments in agricultural technology and practices. Agricultural thinking also progressed, leading to the formation of the San Yi (三宜) principle (adaptation to the season, location, and specific conditions).

In Xu Guangqi's book Complete Treatise on Agriculture (《农政全书》), he explored irrigation, fertilizers, famine relief, economic and textile crops, and observed elements that helped an early understanding of chemistry.

Medicine

Ming China also made significant contributions to the field of medicine. Li Shizhen's (李时珍) Bencao Gangmu (《本草纲目》) is the most famous, a comprehensive medical text comprising 1892 entries, summarizing pharmacology before the 16th century.

Inoculation, originating from traditional Chinese medicine, was documented in Chinese texts by the 16th century, with around fifty texts on smallpox treatment published during the Ming Dynasty. By the 17th century, smallpox inoculation in China had advanced significantly and was widely promoted across the nation.

Culture

Philosophy

Wang Yangming (王阳明) continued Lu Jiuyuan's (陆九渊, 1139-1193) Philosophy of the Heart (心学), emphasizing "conscience" and the unity of knowledge and action, affirming the subjective status of individuals and placing the initiative of "man" at the heart. His disciple Wang Gen (王艮) furthered this discourse, affirming the significance of common people's daily lives. Li Zhi (李贽) emphasized the value of "human desires," linking moral concepts to daily needs.

With the influx of Western learning, the scientific spirit gained traction. Amidst late Ming changes, philosophers like Wang Fuzhi (王夫之), Huang Zongxi (黄宗羲), and Gu Yanwu (顾炎武) focused on practical issues and political reform, while academies flourished, providing platforms for criticism of the political status quo.

Figures like Gu Xiancheng (顾宪成) and Gao Panlong (高攀龙), lecturing at Donglin Academy (东林书院), challenged authority, turning it into a hub of dissent. Scholars also utilized temple grounds for lectures, promoting new ideological values and life perspectives.

Literature

Novels and Short Story Collections

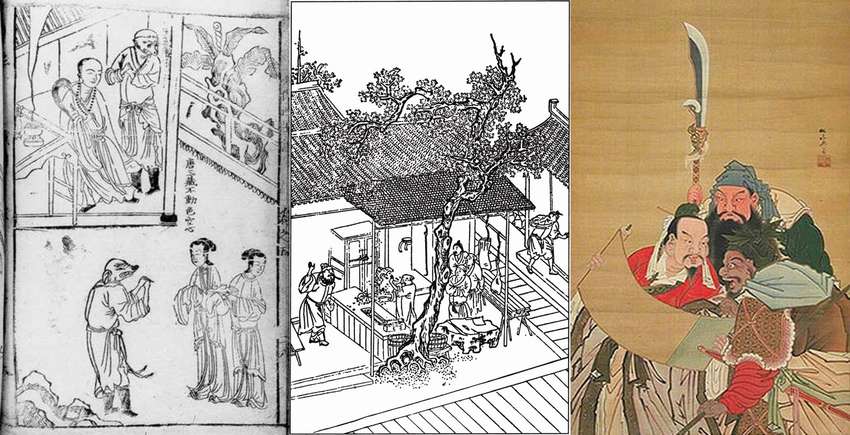

Left: 18th-century Chinese illustration of a scene from Journey to the West.

Middle: illustration from a 15th-century woodcut edition of Water Margin.

Right: three heroes of Romance of the Three Kingdoms, silk painting by Sekkan Sakurai (1715-1790).

Ming's literature reached its pinnacle through novels, including long episodic novels and short story collections covering various themes like history, the supernatural, romance, and urban life.

Journey to the West (《西游记》), Water Margin (《水浒传》), Romance of the Three Kingdoms (《三国演义》) and Jin Ping Mei (《金瓶梅》) that were written around this period are considered classics.

Some literati adapted and reworked stories from the Song and Yuan dynasties and created new ones. Representative works of these adaptations include Three Stories (三言) and Two Slaps (二拍).

Feng Menglong (冯梦龙) compiled the trilogy of vernacular short story collections (known as Three Stories) comprising Stories Old and New (《喻世明言》), Stories to Caution the World (《警世通言》), and Stories to Awaken the World (《醒世恒言》).

Similarly, Two Slaps collections of short stories (two volumes of Slapping the Table in Amazement, 《拍案惊奇》) containing forty short stories each, was compiled by Ling Mengchu (凌蒙初).

Poetry

The development of traditional refined literature continued during the Ming Dynasty, with a plethora of poetry and prose, featuring numerous authors and distinct schools of thought.

The Yongle (永乐) era saw the prevalence of a courtly style (台阁体) praising saintly virtues but lacked vitality. In the Zhengtong (正统) era, Li Dongyang (李东阳) and the former Seven Scholars (前七子) advocated for a return to ancient literary styles, opposing the courtly style. During the Jiajing (嘉靖) era, the latter Seven Scholars (后七子) focused more on formalities in their revivalist movement. Meanwhile, the Tang-Song school (唐宋派) opposed the views of both the former and latter Seven Scholars, advocating for emulation of the works of Tang and Song, and promoting writing to elucidate principles. During the Wanli (万历) period, the Gong'an school (公安派) opposed the emulation of antiquity, advocating for individual expression, while the Jingling school (竟陵派) emphasized "true poetry" and individuality while learning from ancient masters.

Drama

Left: portrait of Tang Xianzu. Right: a scene from The Peony Pavilion.

During the mid-Ming period, with the flourishing urban economy, there emerged new developments in theater greatly enjoyed by the masses, producing many progressive works. The most renowned Ming drama is The Peony Pavilion (《牡丹亭》) by Tang Xianzu (汤显祖).

Popular opera singing styles during the Ming era included Yiyang (弋阳腔) and Kunshan tunes (Kunqu, 昆曲). In the Jiajing era, musician Wei Liangfu (魏良辅) reformed Kunqu, blending southern tunes' delicate characteristics with some of the vigor of northern tunes, making it the most influential theatrical music of the time.

Art

Painting

Left: portraits of the Four Masters of Ming.

Middle: Clearing after Snow on a Mountain Pass by Tang Yin (1470-1524).

Right: Chrysanthemums and Bamboos by Xu Wei (1521-1593).

During the early Ming, court painters dominated the art scene. By the mid-15th century, the emergence of the Four Masters of Wu (吴门四大家) - Shen Zhou (沈周), Wen Zhengming (文征明), Tang Yin (唐寅), and Qiu Ying (仇英) - signaled a shift. Drawing from the strengths of Tang, Five Dynasties, Song, and Yuan painting styles, they developed distinct artistic styles, later became known as the Four Masters of Ming (明四家).

During the Jiajing period, Xu Wei (徐渭) pioneered ink-splashed painting, while in the Wanli era, Zhang Hong (张宏) initiated realistic landscape sketching, innovating upon the established Wu School style with fresh and elegant compositions imbued with ethereal tranquility.

Calligraphy

Semi-cursive and cursive scripts prevailed in calligraphy during the Ming Dynasty.

Early on, calligraphy was entrenched in the conservative courtly style (台阁体), but the Shen brothers, Shen Du (沈度) and Shen Can (沈粲), elevated small regular script (小楷) to its peak, widely adopted by the court and for official documents. Their work set the standard for civil service exams, leading to the dominance of such courtly style.

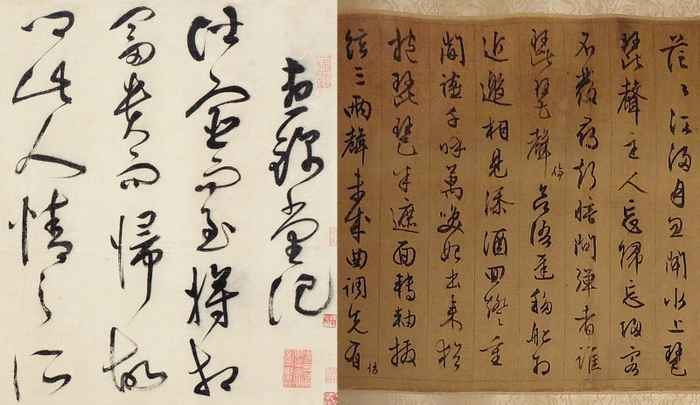

Left: Zhu Yunming's wild-cursive calligraphy: the first part of Zhou Jin Tang Ji.

Right: a part of Wen Zhengming's Pi Pa Xing in the semi-cursive script.

Mid-Ming saw the rise of the Four Masters of Wu, shifting calligraphy towards elegance and refinement. Zhu Yunming (祝允明), Wen Zhengming (文征明), Wang Chong (王宠), and Tang Yin (唐寅) led this shift, fostering a period of personalized expression.

Late Ming witnessed a surge of critical thinking in calligraphy, favoring large-scale works for their dynamic visual impact. Notable figures include Zhang Ruitu (张瑞图), Huang Daozhou (黄道周), and Wang Duo (王铎).

Architecture

The Ming Dynasty achieved remarkable advancements in architecture, particularly evident in the construction of the city walls of Nanjing and Beijing. Nanjing's city walls, completed in 1387, stretched 66 kilometers in circumference, making them the world's longest. The layout of Nanjing's city deviated from the typical square pattern, adapting to geographical features. Conversely, Beijing's city layout reflected an emphasis on imperial authority with its square design.

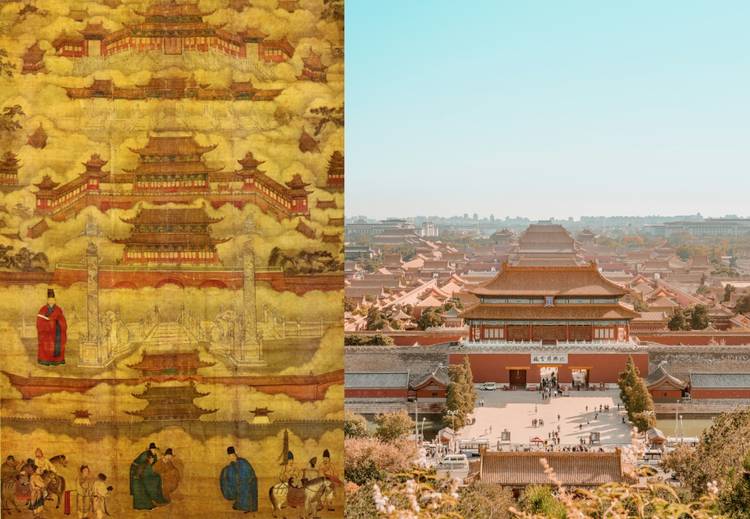

Left: the Forbidden City depicted in a Ming dynasty painting.

Right: a photograph of the Forbidden City.

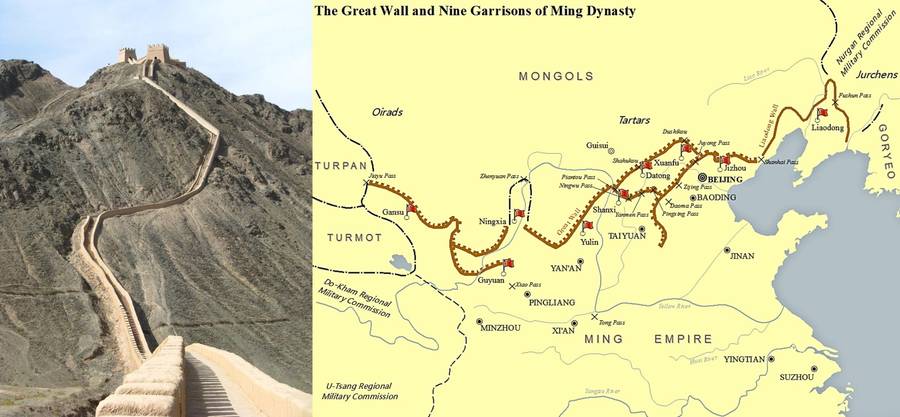

The Ming Dynasty's palace architecture, epitomized by the Forbidden City (故宫 or 紫禁城), was grand. Other imperial structures like the Temple of Heaven (天坛) and the Confucius Temple (孔庙) were equally impressive. The construction of imperial tombs during this era was monumental, and the reconstruction of the Great Wall (万里长城), known as the Ming Great Wall (明长城), stands as an unparalleled masterpiece, safeguarding the borders of the Ming Dynasty and still standing tall to this day.

Left: a section of the Great Wall on the Hanging Cliffs leading up to Jiayu Pass.

Right: the extent of Ming and its walls, forming most of the Great Wall of China.