The Yuan Dynasty (元朝, Yuán), spanning 1279 to 1368, holds a significant place in Chinese history as the first unified empire established by a minority ethnic group, with five generations and eleven emperors in succession.

Genghis Khan (成吉思汗) founded the Mongol Empire in 1206, and in 1271, Kublai Khan (忽必烈) officially named it the Yuan Dynasty. In 1279, the Southern Song Dynasty was conquered by the Yuan Dynasty.

The period saw an unprecedented level of global cultural and economic exchanges, particularly along the Silk Road, integrating China more deeply into the world economy.

Rise of the Yuan Dynasty

The Origin

In the Mongolian plateau region, numerous Mongol tribes were originally vassals of the Jurchen Jin Dynasty (1115-1234). As the Jin declined, the Mongol tribes began to grow in strength, gradually breaking away from Jin's rule. In 1204, Mongol leaders, including Temüjin (铁木真), unified the various Mongol tribes through warfare. In 1206, Temüjin was elected as "Genghis Khan" (成吉思汗, meaning "powerful ruler"), establishing a regime in the northern deserts and founding the Mongol Empire (大蒙古国). From then on, the Mongolian grasslands saw an end to the prolonged period of chaos and warfare.

Portraits of Genghis Khan (left) and Kublai Khan (right)

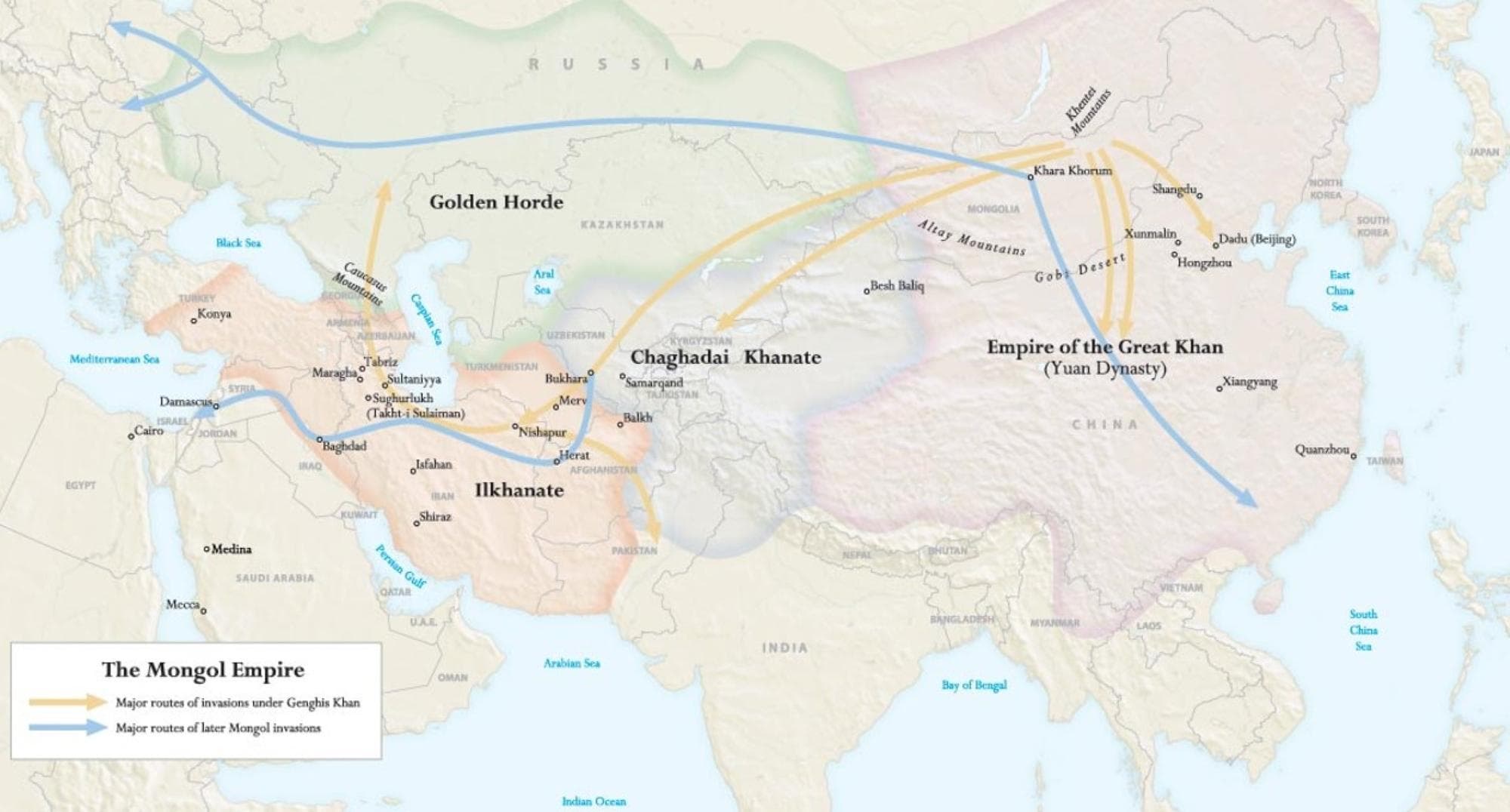

The Mongol Empire

After the establishment of the Mongol Empire, there was a continuous expansion of its territory through external military campaigns. In 1218, the Mongols conquered the Western Liao (西辽). In 1227, they conquered the Western Xia (西夏), and Genghis Khan died during the expedition. In 1234, the Mongols, in alliance with the Southern Song (南宋), completely defeated the Jin Dynasty. In 1241, Mongol forces heading westward briefly approached the heartland of Eastern Europe. In 1244, they subjugated Tibet (吐蕃). In 1253, Kublai Khan led an expedition to the southwest, conquering the Dali Kingdom (大理国).

During external military campaigns, the Mongol armies massacred and enslaved populations in areas that dared to resist, leading to brutal and unjust ethnic oppression. Countless lives and properties were lost in the ravages of war, subsequent plagues, famines, and natural disasters, making it a dark period for the regions affected by conflict.

Map of Mongol successor Khanates

Establishing the Yuan Dynasty

From 1260 to 1264, Kublai Khan (忽必烈), Genghis Khan's grandson, engaged in a four-year war for the supreme rule against his brother Ariq Böke (阿里不哥), ultimately securing the highest position.

In 1271, Kublai Khan officially adopted the title Great Yuan (大元) for the empire. The following year, the capital of the Yuan Empire was established in Dadu (大都, present-day Beijing) in the heartland of the former Jin Dynasty.

After stabilizing the political situation in the north, Kublai Khan decided to initiate an invasion of the Southern Song. In 1279, the Yuan forces annihilated the last resistance of the Song in the Battle of Yamen (崖山海战), marking the unification of the Yuan Dynasty, bringing an end to the prolonged period of division and warfare in China since the late Tang, consolidating and advancing the development of a unified multi-ethnic state.

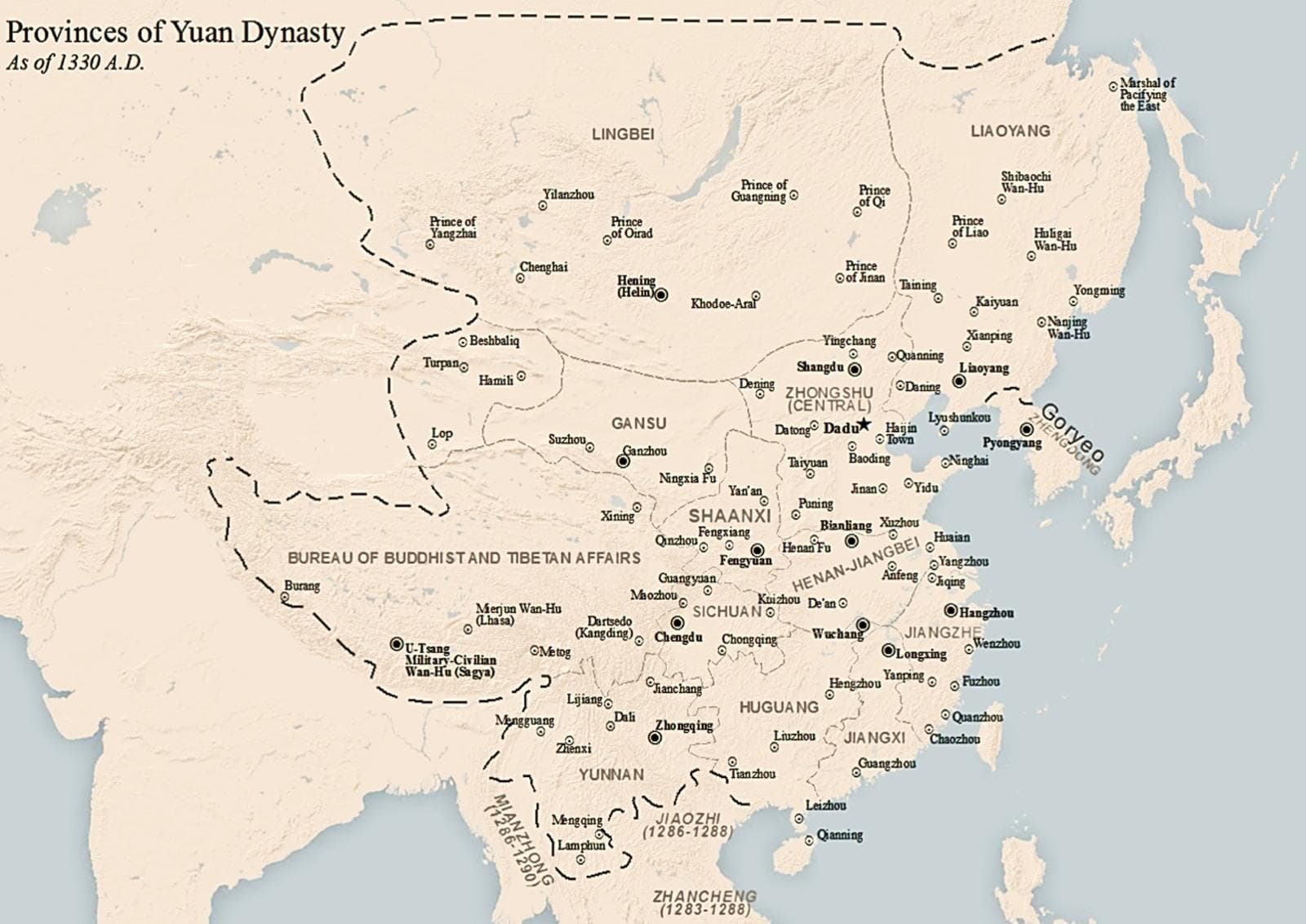

Map of Yuan Provinces in 1330

Politics and Government

The Yuan Dynasty inherited the political system of the Song Dynasty, adopting a division of civil and military powers. The central government was managed by the Central Secretariat (中书省, Zhongshu Sheng), while the Bureau of Military Affairs (枢密院, Shumiyuan) oversaw military affairs.

Conflicts frequently arose between the promotion of Han Chinese legal systems and the preservation of traditional Mongolian laws. This led to a split between conservative factions and those advocating for Han Chinese practices, resulting in frequent conflicts and political upheavals.

Kublai Khan actively promoted Han legal practices. He appointed a large number of Han bureaucrats and Confucian scholars to establish legal systems. When Kublai Khan established the Yuan Dynasty, a political system modeled after traditional Chinese centralized authority was implemented. This included institutions like the Three Departments and Six Ministries (三省六部), adapting ruling structures from the Central Plains to govern the people. However, the four major khanates and the conservative factions within the Mongolian royal family were dissatisfied with Kublai Khan's adoption of Han practices, leading to betrayals and estrangements.

As for talent selection, although many systems were inherited from the Song Dynasty, there was no regular and institutionalized imperial examination system in the early Yuan. The appointment of high-ranking officials depended largely on their proximity to the Yuan court, and appointments were mainly done through hereditary succession, favoritism, and recommendations. It wasn't until 1313, during the Sinicization movement advocated by Emperor Renzong of Yuan (元仁宗), that the imperial examination system was reinstated.

To uphold the autocratic rule of the Mongol nobility, a four-class social structure was established, with the Mongol elite at the top, followed by Central Asian allies (Semu, 色目人), Northern Chinese (Han, 汉人) and Southerners (Nan, 南人) at the bottom of the hierarchy. This resulted in a series of unequal policies and regulations.

Four-Class System

| Class (high to low) | Chinese | Ethnicity |

| Mongols | 蒙古人 | Citizens of the ruling empire |

| Semu | 色目人 | Non-Mongol foreigners from the west and Central Asia |

| Han | 汉人 | Han Chinese people in Northern China |

| Nan | 南人 | Southerners, or people of the former Southern Song Dynasty |

*Generally, Han (汉人) refers to all Han Chinese, but Yuan differentiates Northern (Han class) and Southern (Nan class) Han Chinese people.

For instance, the number of candidates for the imperial examination among Mongols and Semu was significantly fewer than that for Han Chinese people (both Han and Nan classes). However, to ensure quotas, a differentiated system was introduced, and extra quotas for Mongols and Semu were reserved beyond their proportional representation.

Moreover, Han Chinese are prohibited from hunting, practicing martial arts, possessing weapons, participating in religious gatherings, engaging in business during markets and fairs, and walking at night.

Economy

The Yuan's economy exhibited a diverse structure and was notably active and developed.

Primarily agrarian, some argue that although the overall productivity might not have matched that of the Song, significant progress was made in terms of production technology, cultivated land area, grain yields, extensive water conservancy projects, and the widespread cultivation of cotton.

Originally a nomadic people heavily reliant on animal husbandry, the Mongols had a single-minded economic focus and no distinct land system. During the Mongol-Jin War, the minister Yelü Chucai (耶律楚材) proposed preserving Han Chinese agricultural production to generate fiscal revenue, a suggestion adopted by Genghis Khan. Subsequently, under Ögedei Khan (窝阔台), measures encouraging production and pacifying refugees were implemented to consolidate control over Han territories, leading to a gradual recovery in agricultural production.

The cultivation of economic crops, especially cotton, was widely promoted, resulting in increased cultivation and marketing of cotton and cotton textiles in the Jiangnan region, building on the foundations laid by the Southern Song. The development of commercial production of economic crops introduced certain elements of commodity and monetary relationships into what was largely a self-sufficient rural economy at the time. However, due to the Yuan's centralized control over numerous artisans engaged in crafting daily necessities, state-operated handicrafts thrived, placing constraints on private handicrafts.

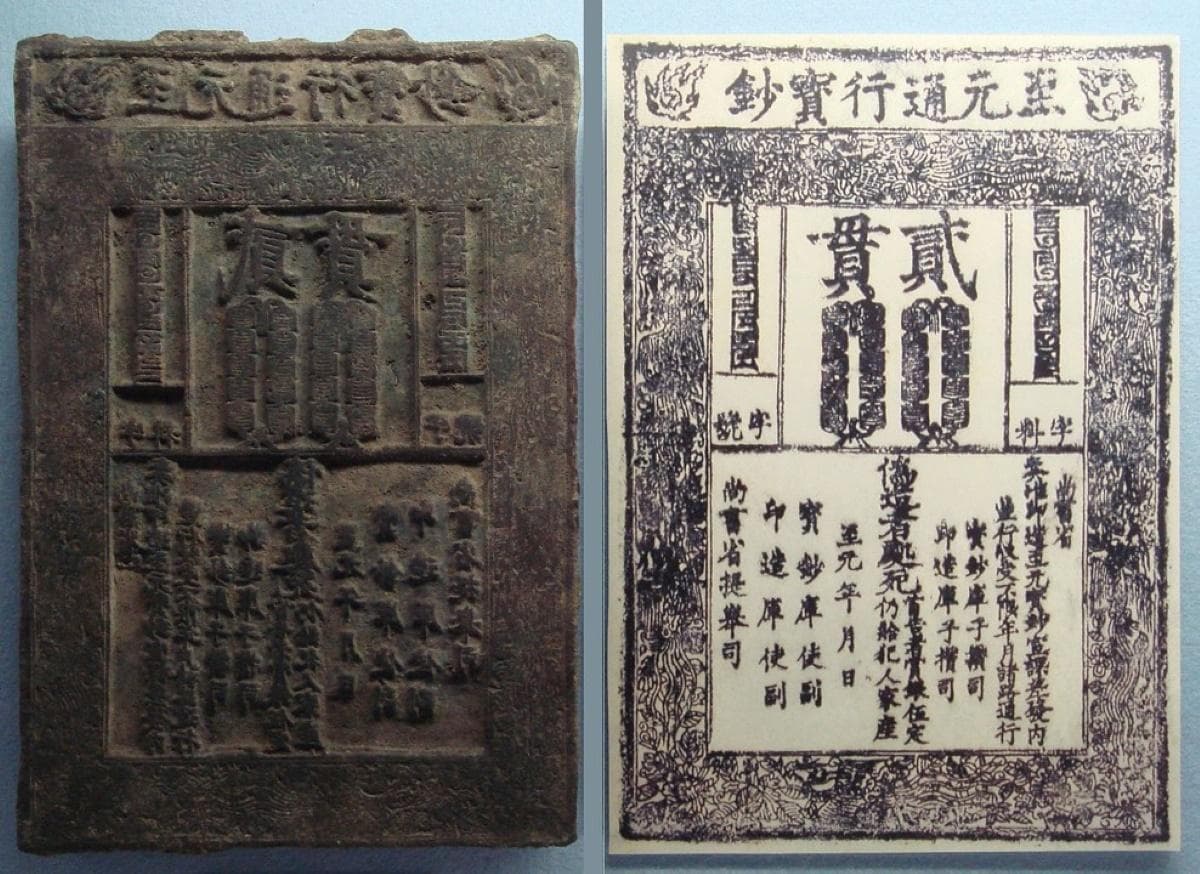

Yuan Dynasty banknote with its printing plate, 1287

Due to the Mongols' reliance on commodity exchange and their limited influence from Confucian anti-commercial sentiments, the Yuan was relatively supportive of commerce, leading to a flourishing commodity economy that made it one of the wealthiest nations at the time. The capital, Dadu, became a renowned global commercial center. To accommodate commodity exchange, the Yuan established the world's earliest fully circulating paper currency system, marking the first dynasty in Chinese history to rely entirely on paper currency for circulation. However, the excessive issuance of paper money led to severe inflation.

The promotion of commodity exchange also facilitated the development of transportation, improving land and water transport through river and maritime routes.

Science and Technology

Due to the Yuan's promotion of diverse ideologies within the court and society, a developed economy providing reliable material support and unprecedentedly active domestic and foreign interactions, conditions were created for the absorption of technological advancements from around the world. This environment led to significant achievements in science and technology, particularly in fields such as astronomy and calendar systems, mathematics, agriculture, animal husbandry, medicine, and geography.

Inventions such as printing technology and gunpowder saw advancements, leading to the development of technologies like movable type printing and firearms, which, upon spreading to the West, contributed to progress in European nations. Achievements in astronomy and medicine from Persia and the Arab world, known for their advancement, were also widely transmitted to China during the Yuan Dynasty.

The flourishing of East-West trade brought a continuous influx of precious goods such as jade, textiles, food, and exotic birds and animals from the Western regions into China. The robust exchange of scientific and technological knowledge between regions facilitated mutual progress, and the Yuan Dynasty, with its favorable conditions, provided an environment for such exchanges superior to previous dynasties.

Culture

Although the Yuan Dynasty was characterized by deep divisions and tension between the ruled and the rulers, it was a period of tremendous cultural interaction. Kublai Khan encouraged the expression of diverse traditions, creativity, and innovation.

The court welcomed foreign visitors, the most famous being Marco Polo, and their cross-cultural interactions led to an upsurge in literature, theater, and art. The era is particularly celebrated for its developments in drama and the novel.

La cite de Caitan (the city of Zayton, a port of Quanzhou in Yuan Dynasty) from a 15th century manucript of Marco Polo's Li livres du Graunt Caam (The Travels of Marco Polo).

Philosophy

The Yuan Dynasty exhibited a nearly impartial acceptance and promotion of various schools of thought. However, there was a certain degree of respect for Confucianism, particularly the Neo-Confucianism that had developed during the Song Dynasty, which was highly esteemed as the official doctrine. In the early years of Emperor Renzong's (元仁宗) reign, the imperial examination system was reinstated, and the examinations specified the use of commentaries by Southern Song Confucian scholars such as Zhu Xi (朱熹). This practice influenced the later imperial examination system during the Ming Dynasty (明朝).

Literature

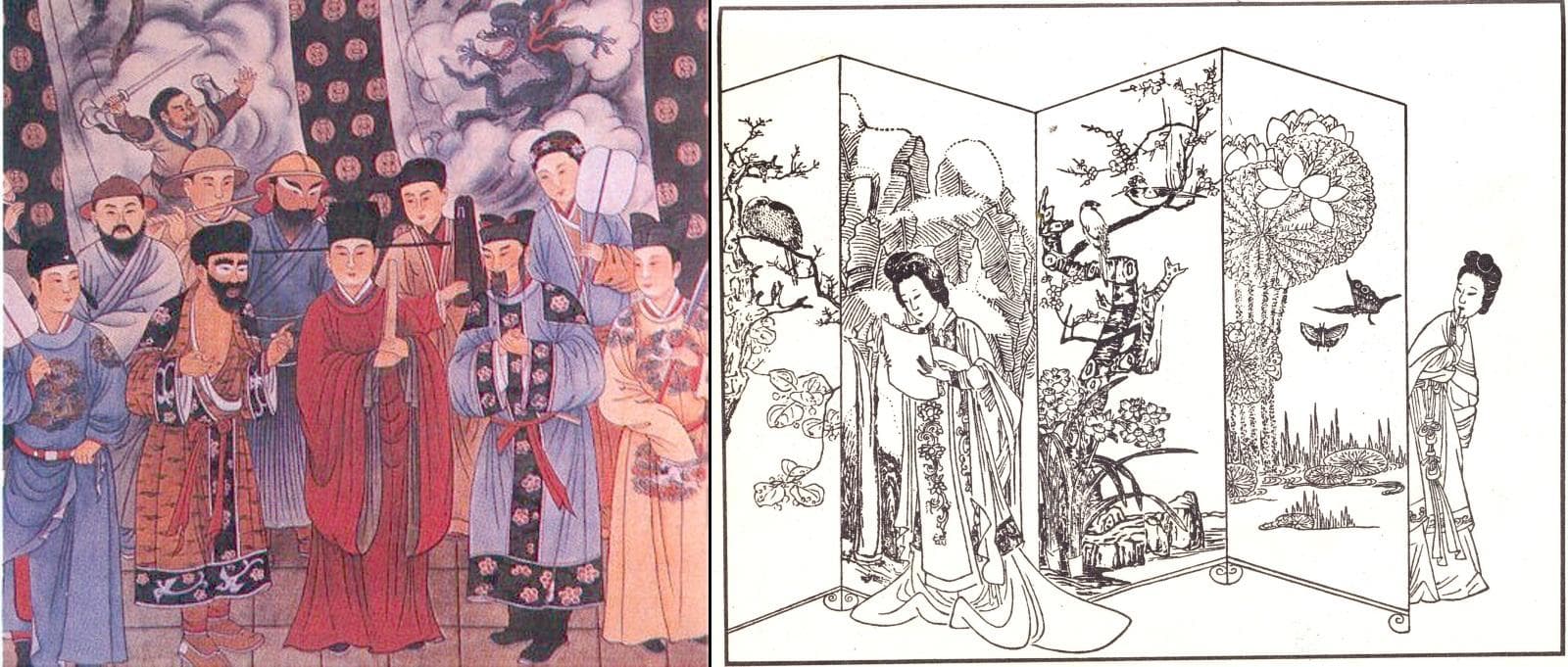

Literary works during this period were primarily dominated by Yuanqu (元曲, Qu poetry and opera of Yuan) and novels, while achievements in poetry were relatively scarce.

Given the prosperity of urban economies during that time, the Yuan court paid less attention to traditional Chinese literature and the imperial examination system. Society, on the other hand, promoted song, dance, and drama as popular entertainment, leading to the transformation and elevation of traditional dramas since the Song and Jin dynasties into Yuanqu.

Left: modern reconstruction of a mural depicting the Yuan Zaju stage (1324).

Right: an illustration of a scene from The Romance of the West Chamber by Chen Hongshou (a 1639 edition).

Yuanqu could be divided into Sanqu (散曲, "literary song") and Zaju (杂剧, a form of opera).

Sanqu, a new form of poetry, served as a form of lyrical expression primarily for popular songs performed on stage. Representative figures included Guan Hanqing (关汉卿) and Ma Zhiyuan (马致远), with notable works like Tianjingsha · Autumn Thoughts (《天净沙·秋思》).

Zaju represented Yuan-era opera. Famous works include The Injustice to Dou E (《窦娥冤》) and Romance of the Western Chamber (《西厢记》).

The flourishing of Yuanqu eventually became one of China's outstanding literary legacies, alongside Han fu (汉赋), Tang poetry (唐诗), and Song ci (宋词).

Yuan's novels evolved from spoken dialogues of stage plays into vernacular storytelling, eventually becoming written novels. Famous examples include Romance of the Three Kingdoms (《三国演义》) and Water Margin (《水浒传》), which are two of the Four Classic Chinese Novels (中国四大名著).

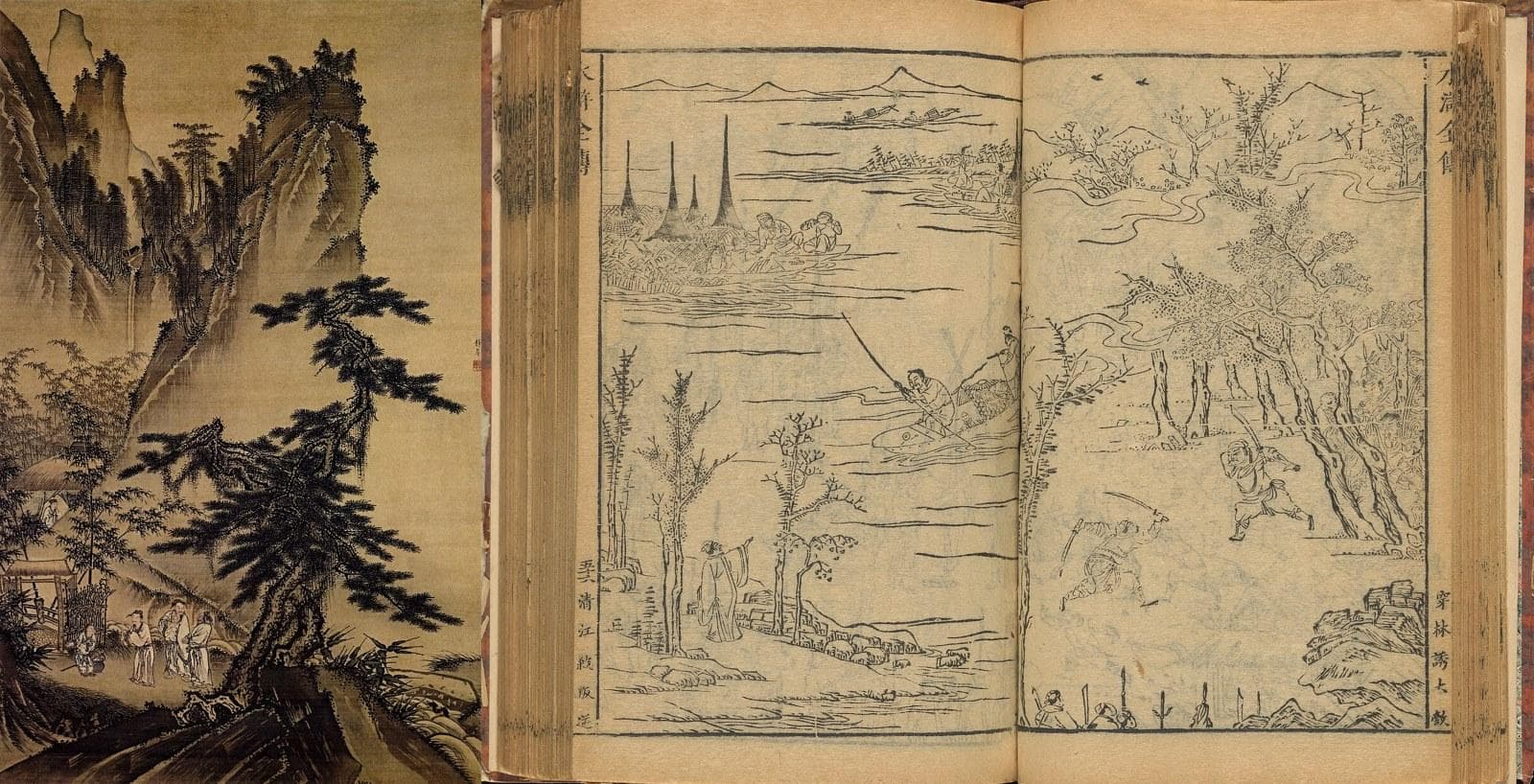

Left: Liu Bei recruiting Zhuge Liang, a scene from Romance of the Three Kingdoms, a Ming Dynasty painting by Dai Jin (1388-1462).

Right: illustrations in a 1610 edition of Water Margin depicting Wang Qing crossing the river.

Religion

The Yuan Dynasty's wide-ranging cultural policy allowed a diverse range of religions to be practiced. Buddhism (particularly Tibetan Buddhism) continued playing an important role, while Islam was prominent among the Mongols and their allies. Christianity, Daoism, and Confucianism were also practiced.

Decline and Fall of the Yuan Dynasty

Although the Yuan Dynasty achieved considerable success, it also faced challenges. The Yuan administration struggled to establish control over the vast territories under its rule. Mongol rulers escalated their imposition of various intricate taxes on the Han Chinese, intensifying ethnic oppression to a severe degree. The Han people faced widespread plunder, and the classification of different ethnic groups into distinct hierarchies led to the brutal exploitation of the Han populace.

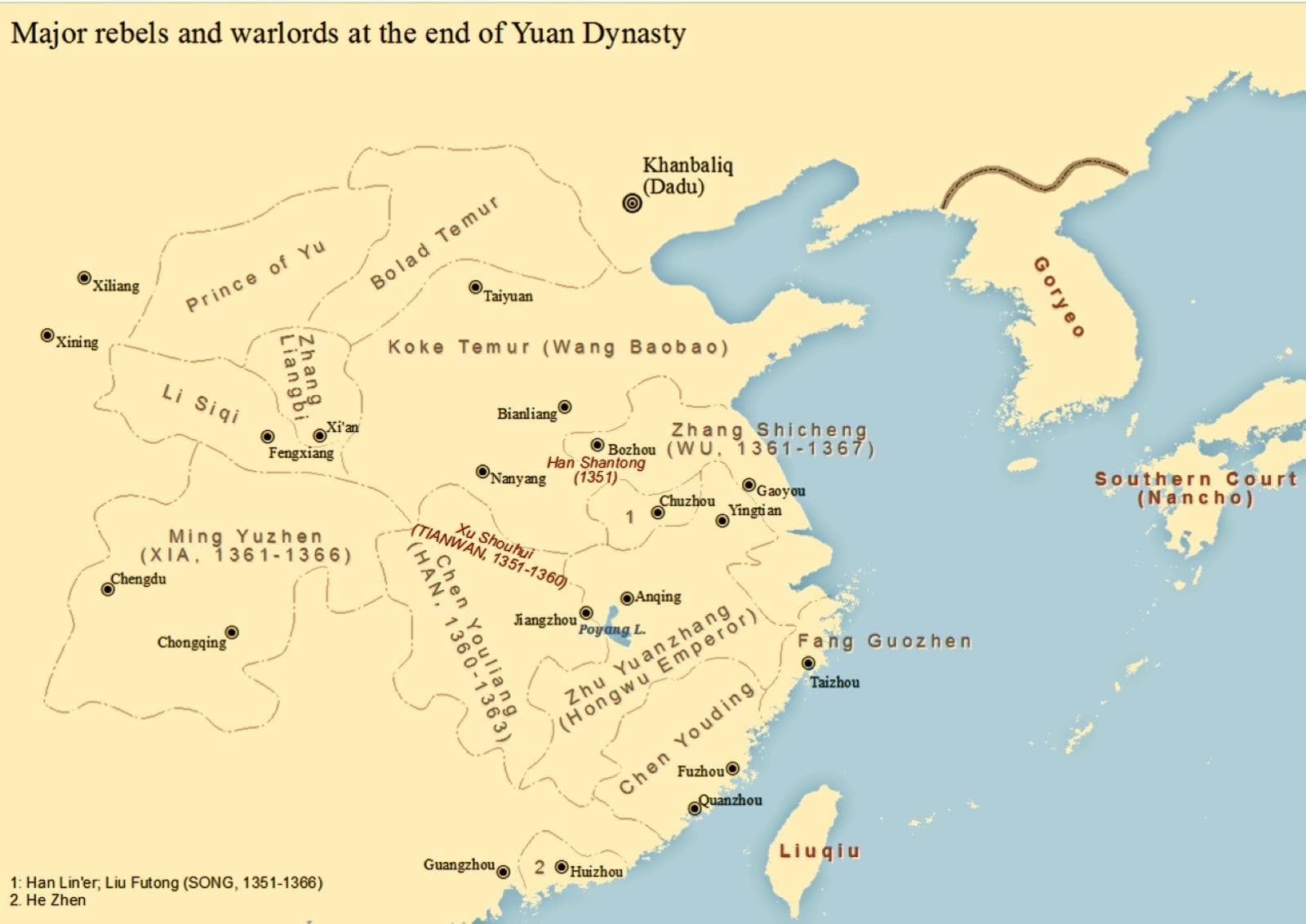

Moreover, natural disasters, corruption, inflation, and famine plagued the dynasty towards its late period. Simultaneously, internal conflicts within the Mongol ruling class, driven by power struggles and personal interests, hastened the decline of the Yuan Dynasty.

Major rebels and warlords at the end of the Yuan Dynasty

Growing public dissatisfaction led to an avalanche of uprisings. Among these rebels, Zhu Yuanzhang (朱元璋), a peasant leader who was part of the Red Turban Rebellions (红巾起义军), overpowered his rivals and finally toppled the Yuan Dynasty in 1368. He founded the Ming Dynasty (Míng, 明朝) and pushed the remnants of the Yuan government back to the Mongolian steppes.