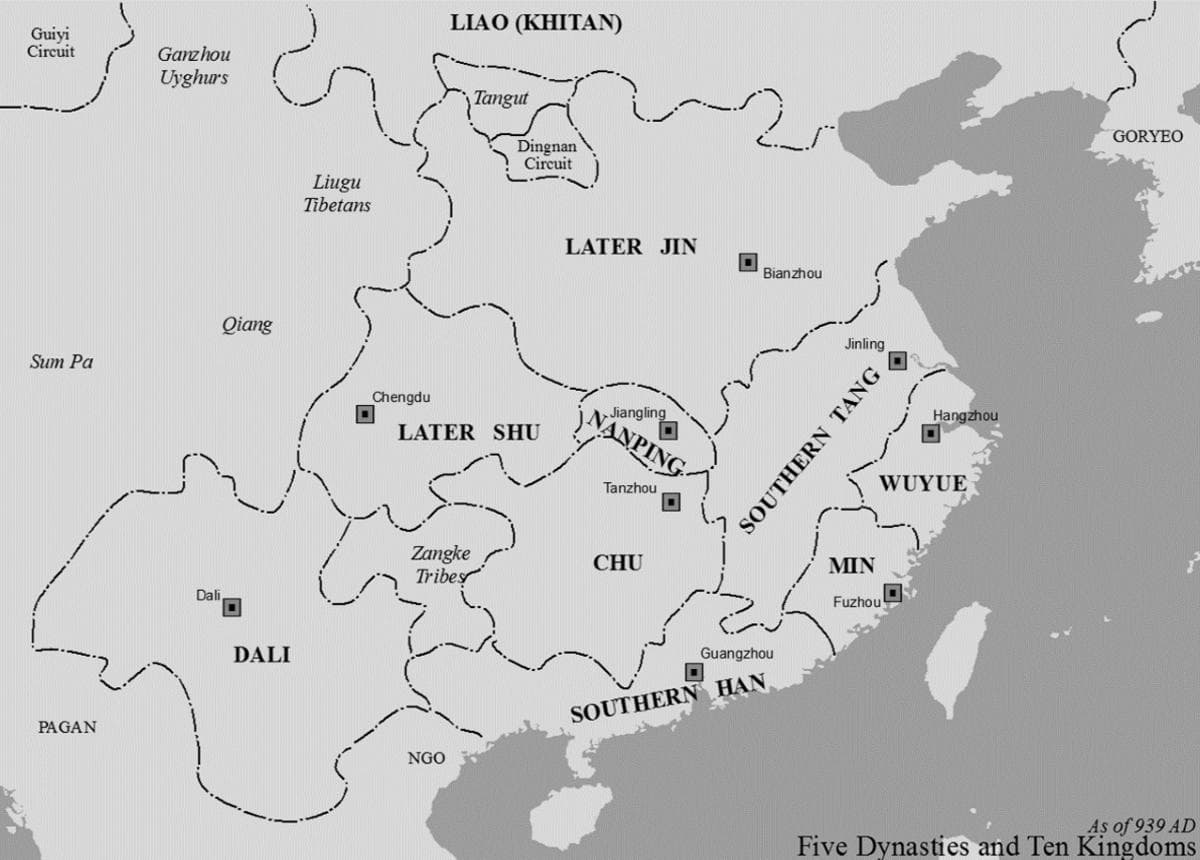

The Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (五代十国, 907-979 CE) was a pivotal era in Chinese history characterized by political upheaval, fragmentation, and the emergence of multiple regimes vying for power. Following the fall of the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE), this era witnessed the rise and fall of five short-lived dynasties in the Central Plain, and other concurrent dynastic states mainly in Southern China, collectively known as the Ten Kingdoms, leading to a complex geopolitical landscape. It was a time of transition from the Tang Dynasty to the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE).

Background

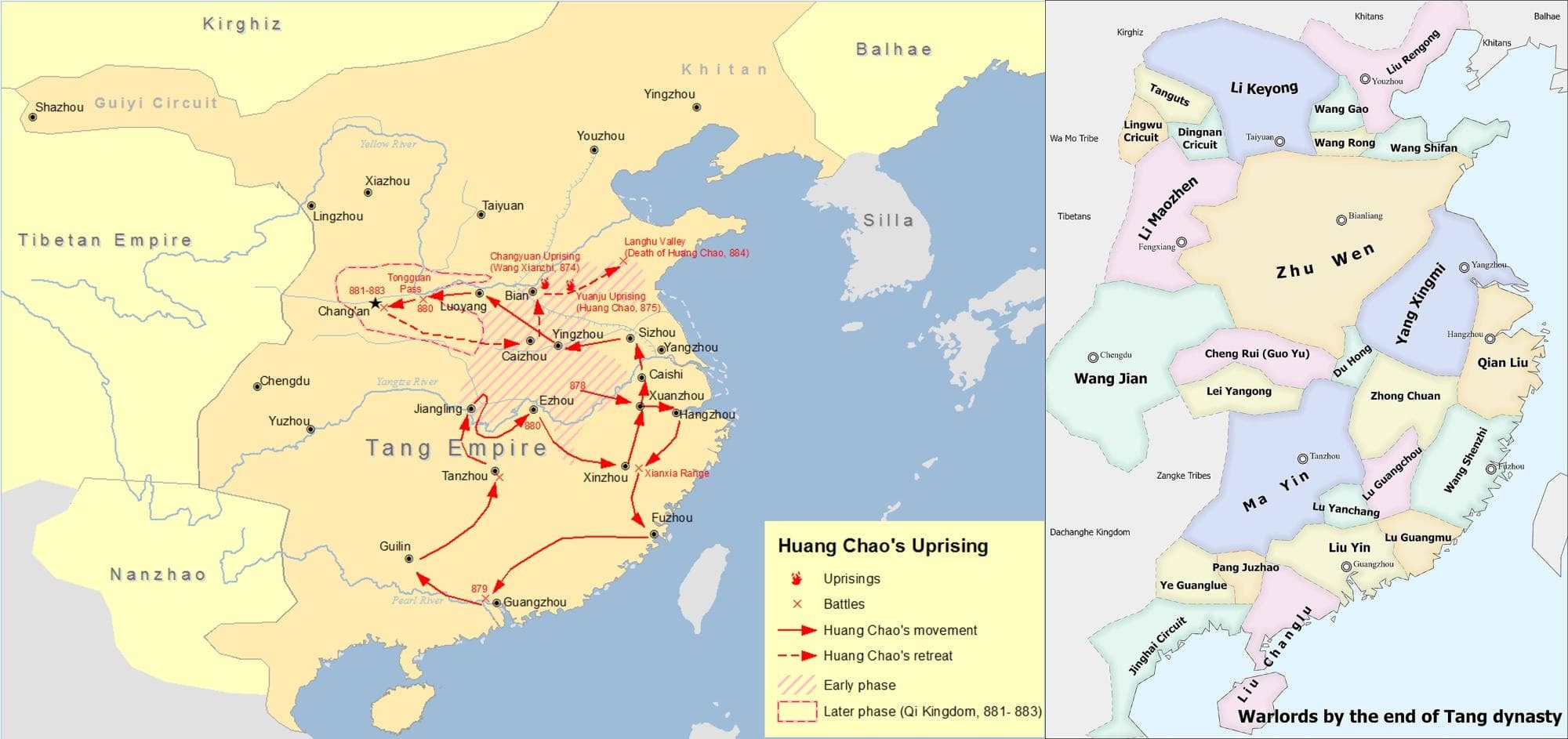

Left: Huang Chao's uprising against Tang (878-884 CE). Right: map of warlords (jiedushi) in 902 CE.

After the Huang Chao Rebellion (黄巢起义), the Tang Dynasty saw the rise of regional military governors (or jiedushi, 节度使), some of whom were granted royal titles and established autonomous kingdoms. After Tang's collapse, this led to the emergence of the Five Dynasties, where strong factions vied for control. These dynasties held power over the Central Plain (中原) consecutively, but they lacked the ability to govern the entire nation. Meanwhile, other regions were ruled by local leaders, some of whom declared themselves emperors and others recognized the Five Dynasties' legitimacy.

Five Dynasties (五代, 907-960 CE)

The Five Dynasties were dynastic states that emerged and established in the Central Plain successively, starting from 907 CE. These dynasties were Later Liang (后梁), Later Tang (后唐), Later Jin (后晋), Later Han (后汉), and Later Zhou (后周). This era came to a close when Zhao Kuangyin (赵匡胤) established the Northern Song Dynasty (北宋) in 960 CE.

Later Liang (后梁, 907-923 CE)

Later Liang in 907 CE

The Later Liang Dynasty marked the beginning of the Five Dynasties period in China. Established by Zhu Wen (朱温) in 907 CE after receiving the abdication of Emperor Ai of Tang (唐哀帝), the Later Liang ended the Tang Dynasty's rule.

Zhu Wen was initially a general under Huang Chao (黄巢), but later surrendered to Tang and was appointed as the Xuanwu Jiedushi (military governor of Xuanwu, 宣武军节度使). In 888 CE, he defeated Qin Zongquan (秦宗权) and took control of the Central Plain. In 904 CE, Zhu Wen moved the Tang court to Luoyang and assassinated Emperor Zhaozong (唐昭宗), securing central authority. In April 907 CE, Zhu Wen accepted Emperor Ai's abdication and established the Later Liang Dynasty.

However, the Later Liang was plagued by internal conflicts, and ultimately fell to its long-standing rival Li Cunxu (李存勖), Emperor Zhuangzong of Later Tang (唐庄宗), in 923 CE.

The territorial extent of Later Liang was the smallest among the Five Dynasties, and its borders were unstable due to frequent conflicts.

Later Tang (后唐, 923-936 CE)

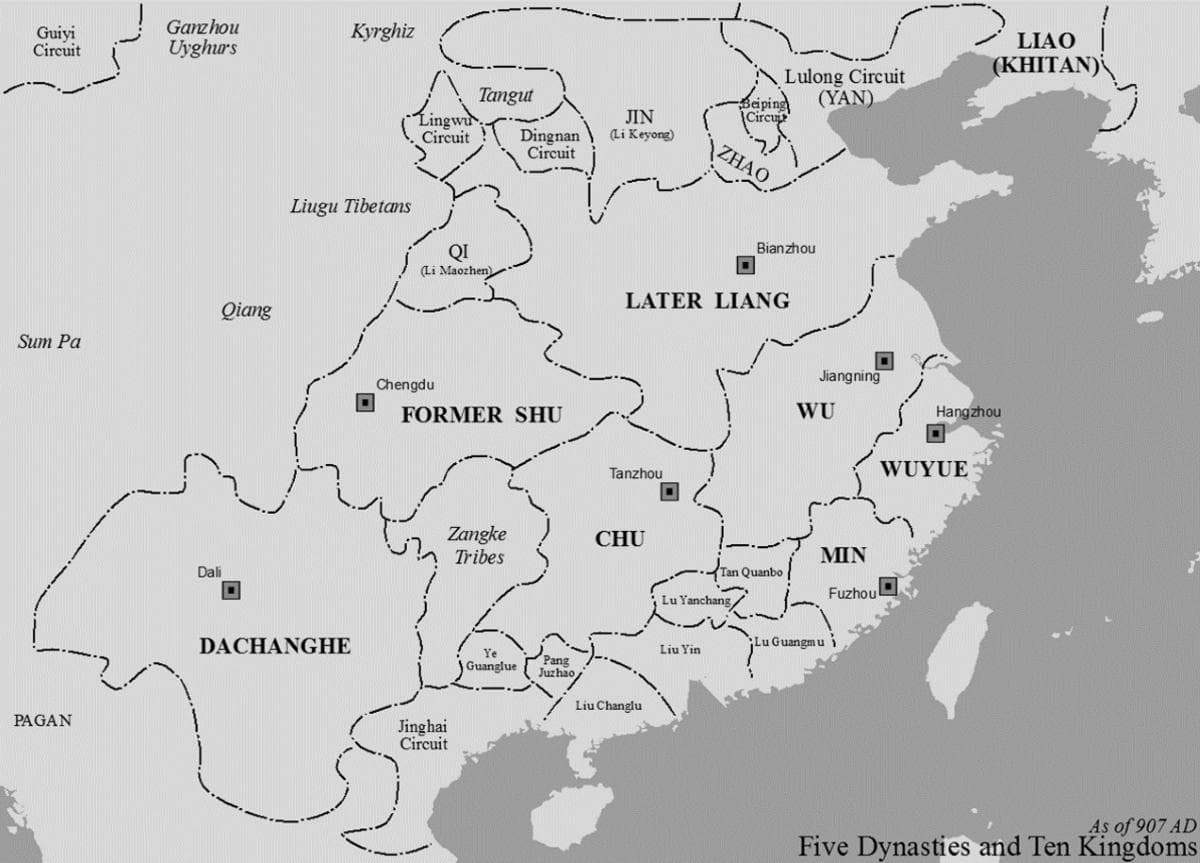

Later Tang in 926 CE

In 896 CE, Li Keyong (李克用), the Hedong Jiedushi (河东节度使), was granted the title of Prince of Jin (晋王). After Zhu Wen usurped Tang's throne and founded Later Liang, Li Keyong's Jin state became the most powerful regional power in the north. He considered Later Liang illegitimate and continued to acknowledge the legitimacy of the Tang Dynasty.

Upon Li Keyong's death in 908 CE, his son Li Cunxu (李存勖) inherited as Prince of Jin. In 923 CE, Li Cunxu declared himself emperor and retained the "Tang" dynasty name. He subsequently overthrew Later Liang and established the Later Tang Dynasty. In the same year, Li Maozhen (李茂贞), the Prince of Qi (岐王), declared his allegiance to Later Tang.

During its existence, Later Tang expanded its control over a vast territory, primarily in northern China. From 925 to 933 CE, most southern states recognized Later Tang's authority, except for Southern Wu (南吴) and Southern Han (南汉). By 930 CE, Later Tang's territorial control reached its peak.

However, Later Tang's reign ended in 936 CE when Shi Jingtang (石敬瑭) used the assistance of Khitan forces (Liao, 辽) to establish the Later Jin Dynasty (后晋).

Later Jin (后晋, 936-947 CE)

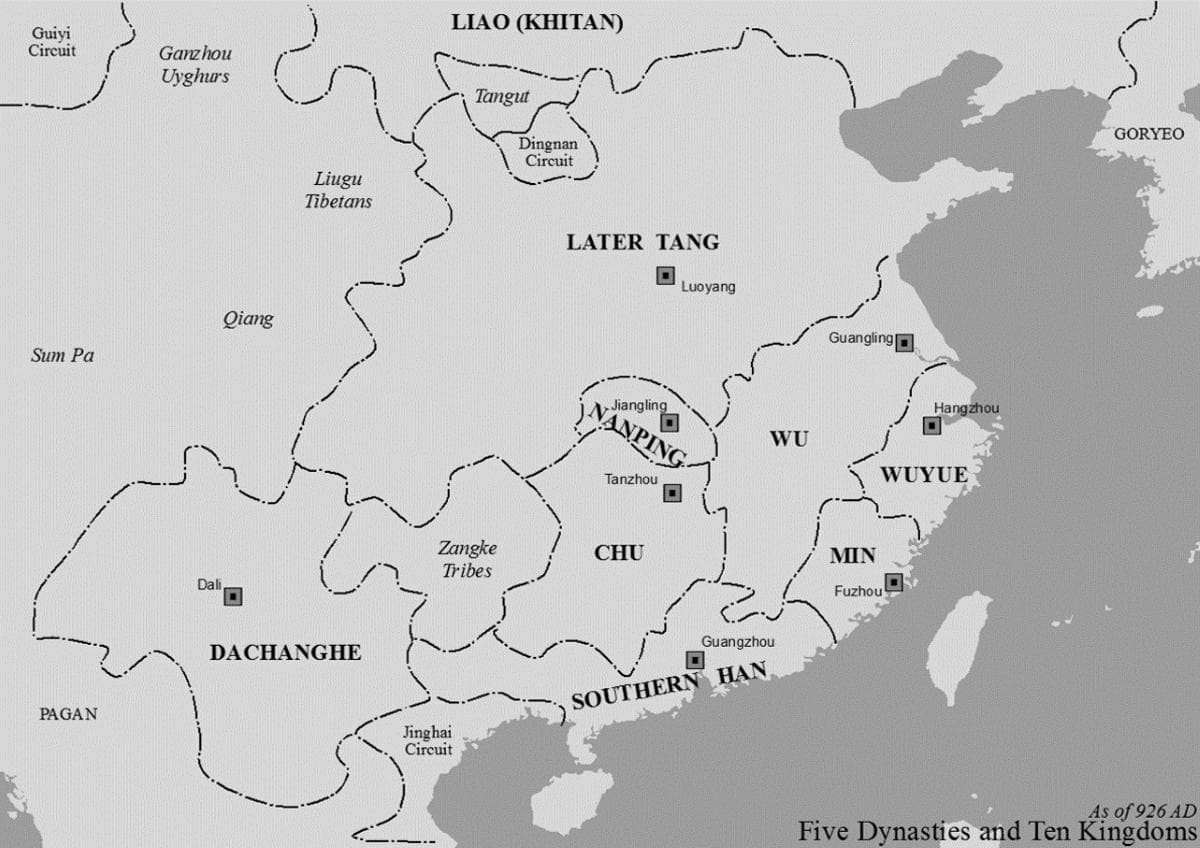

Later Jin in 939 CE

In 936 CE, Shi Jingtang (石敬瑭), the Hedong Jiedushi (河东节度使), colluded with the Khitan-led Liao Dynasty (辽) and acknowledged Khitan Emperor Yelü Deguang (耶律德光) as his father. In exchange for the Sixteen Prefectures of Yanyun (燕云十六州), he ascended the throne with Khitan support, establishing the Later Jin Dynasty. He soon overthrew Later Tang.

However, his controversial practice of ceding territory in exchange for power faced opposition, even from former allies, setting the stage for Later Jin's downfall.

Upon Shi Jingtang's death, his nephew Shi Chonggui (石重贵) succeeded him. Shi Chonggui gradually distanced himself from Khitan influence, initially claiming to be a descendant of Yelü Deguang but refraining from swearing allegiance.

From 944 to 947 CE, the Khitan launched three invasions to Later Jin. Despite initial successes against invasions, Later Jin faced a major blow in 947 when a key official defected to the Khitan. Under pressure, Shi Chonggui surrendered, leading to the collapse of Later Jin. Subsequently, Liu Zhiyuan (刘知远) declared himself emperor and established the Later Han Dynasty (后汉).

Later Han (后汉, 947-950 CE)

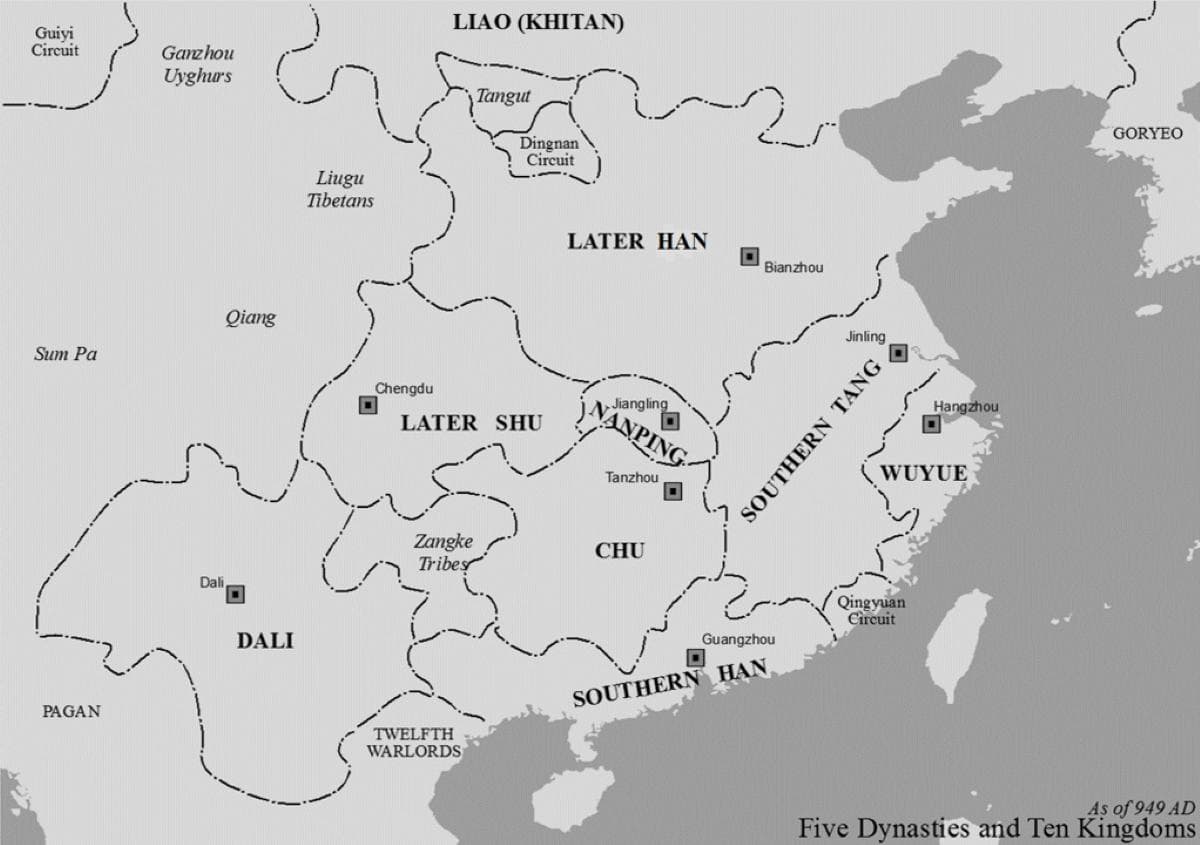

Later Han in 949 CE

Established by Liu Zhiyuan (刘知远), the Later Han Dynasty was the shortest among the Five Dynasties, which lasted only 3 years. Its brevity and limited territorial control showcased the period's instability.

Liu Zhiyuan was appointed as the Hedong Jiedushi (河东节度使) by Shi Jingtang (石敬瑭) during Later Jin. In 947 CE, after the Khitan conquered Later Jin and occupied the Central Plain, their brutal actions caused widespread discontent among the people, leading them to eventually retreat. Later that year, Liu Zhiyuan seized the opportunity and declared himself emperor, and established the Later Han Dynasty.

In 948 CE, Liu Zhiyuan passed away, and his second son, Liu Chengyou (刘承祐), succeeded the throne. In 950 CE, a rebellion erupted among regional military leaders. Liu Chengyou ordered Guo Wei (郭威) to suppress the rebellion, but he grew suspicious of Guo Wei's intentions and attempted to have him killed. In response, Guo Wei rebelled, and Liu Chengyou was killed by his own fleeing soldiers, marking the end of Later Han.

Later Zhou (后周, 951-960 CE)

Later Zhou in 951 CE

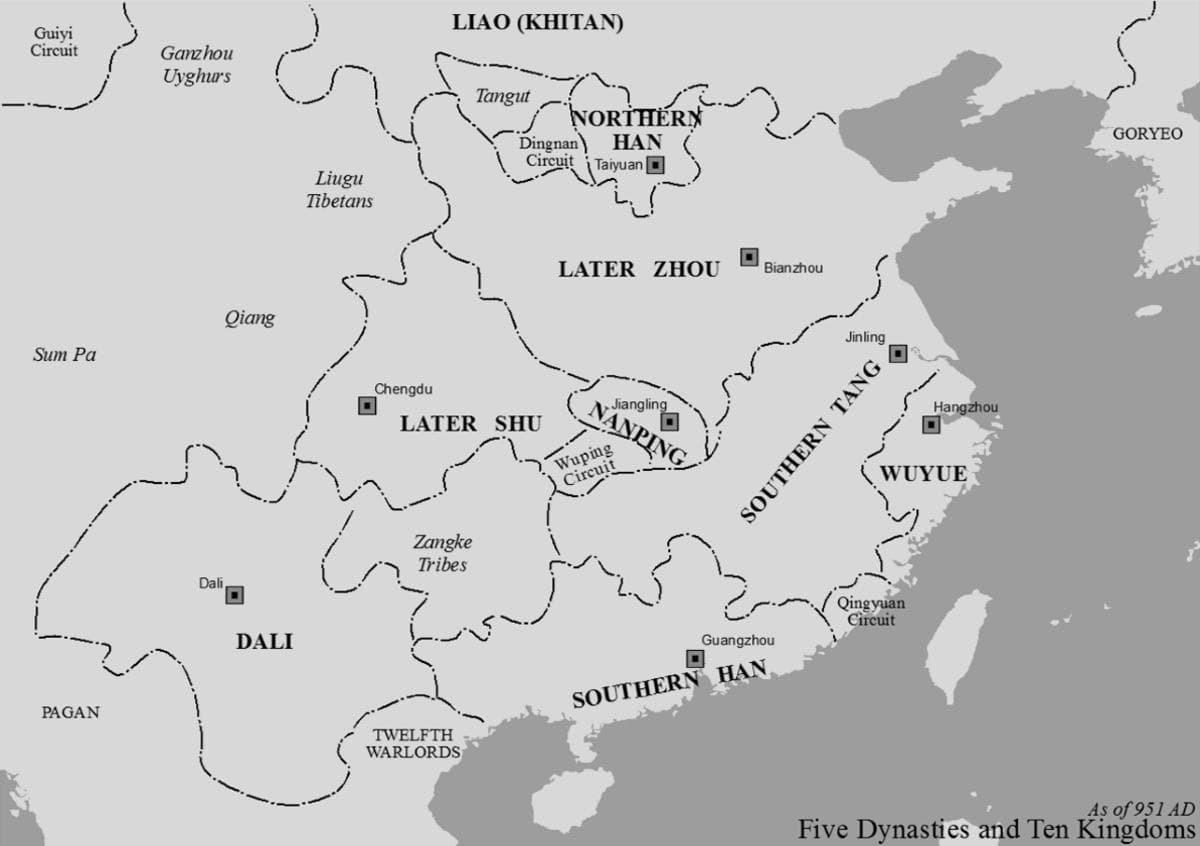

The Later Zhou Dynasty was the last of the Five Dynasties.

Later Zhou's founder Guo Wei (郭威) emerged after he rebelled against Emperor Yin of Later Han (汉隐帝), Liu Chengyou (刘承祐). After seizing power, Guo Wei implemented reforms such as reducing corvée labor, improving military discipline, and combating corruption, setting the foundation for subsequent military endeavors during the Later Zhou Dynasty.

In 954 CE, Guo Wei passed away, and his adopted son, Chai Rong (柴荣), ascended the throne as Emperor Shizong of Later Zhou (周世宗). Emperor Shizong successfully defended against attacks from Northern Han (北汉) during the Battle of Gaoping (高平之战), stabilizing his rule. Through reforms within the imperial army, he enhanced the military's combat capabilities.

From 955 to 958 CE, Emperor Shizong launched campaigns against Southern Tang (南唐), forcing it to relinquish its imperial title and cede territory north of the Yangtze River. He also sent troops to conquer parts of Later Shu (后蜀), acquiring multiple provinces.

In 959 CE, Emperor Shizong launched a northern campaign against the Khitan-led Liao Dynasty (辽), and successfully recovered some of the territories ceded during Later Jin. However, Emperor Shizong succumbed to illness and passed away in the same year, and his young son, Chai Zongxun (柴宗训), succeeded him as Emperor Gong of Later Zhou (周恭帝).

In 960 CE, Zhao Kuangyin (赵匡胤), a general of the imperial army, initiated the Chenqiao Coup (陈桥兵变), compelling Emperor Gong to abdicate the throne. He established the Northern Song Dynasty (北宋), marking the end of Later Zhou.

Ten Kingdoms (十国, 902-979 CE)

During the late Tang Dynasty, the Five Dynasties, and the early Northern Song Dynasty, numerous fragmented regimes emerged beyond the Central Plain. Among these, ten separatist powers (see below) were collectively referred to as the Ten Kingdoms by the Historical Records of the Five Dynasties (《新五代史》) and subsequent historians.

Unlike the Five Dynasties of the Central Plain which succeeded one after another, the Ten Kingdoms were generally concurrent, each controlling a specific geographical area.

The Ten Kingdoms were:

| Regime | Chinese | Duration (CE) |

| Wu/Southern Wu/Yang Wu | 南吴/杨吴 | 902-937 |

| Southern Tang | 南唐 | 937-975 |

| Wuyue | 吴越 | 907-978 |

| Min | 闽国 | 909-945 |

| Southern Chu/Ma Chu | 南楚/马楚 | 907-951 |

| Former Shu | 前蜀 | 907-925 |

| Later Shu | 后蜀 | 934-966 |

| Jingnan/Nanping | 荆南/南平 | 924-963 |

| Southern Han | 南汉 | 917-971 |

| Northern Han | 北汉 | 951-979 |

Among the Ten Kingdoms, all were regimes in South China except for Northern Han (北汉).

Southern Wu (南吴) was initially the most powerful in the Jiangnan area (江南), but it was later overthrown by Southern Tang (南唐). Then there were significant powers such as Wuyue (吴越) and Min (闽国). The region of Huguang (湖广) was divided among Jingnan (荆南), Southern Chu (南楚), and Southern Han (南汉). Southern Tang stood out as one of the strongest among the Ten Kingdoms, conquering both Min and Southern Chu. However, continuous military conflicts weakened its strength, and it was eventually defeated by Later Zhou.

In the Sichuan region, there were two Shu states: Former Shu (前蜀) and Later Shu (后蜀). They were relatively prosperous and powerful, second only to Southern Tang. Despite their strength, they ultimately fell due to complacency and internal strife.

Northern Han was the only one among the Ten Kingdoms situated in the northern region. It was established by descendants of Later Han.

After Zhao Kuangyin (赵匡胤) established the Northern Song Dynasty (北宋), he and his brother successively subdued various warlords. By 979 CE, they unified most of China except for Jiaozhou (交州) and the Sixteen Prefectures of Yanyun (燕云十六州), bringing an end to the Ten Kingdoms era.

Culture

The Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms era marked a transition from Tang's international cultural fusion to a precursor of Song's distinct national culture. Despite the political turmoil, it saw cultural and economic growth rather than decline.

Literature

For poetry (诗, Shi), this era's notable poets included Du Xunhe (杜荀鹤) of Later Liang, Han Wo (韩偓) of Min, Luo Yin (罗隐) of Wuyue, Wei Zhuang (韦庄) and Buddhist monk Guanxiu (贯休) of Former Shu. Most of these poets hailed from the late Tang era or the early Five Dynasties and reflected the tumultuous times and sufferings of the people in their works.

Notably, this period was a crucial stage in the development of Ci poetry (词). The relative calm and socio-economic prosperity in regions like Former Shu, Later Shu, and Southern Tang fostered many skilled ci poets.

Two centers of Ci poetry emerged.

The Shu region (Former and Later Shu) produced figures like Wei Zhuang (韦庄) and Ouyang Jiong (欧阳炯), whose works were influenced by the graceful and charming style of the late Tang Ci poet Wen Tingyun (温庭筠). They often described the indulgent lives of the ruling class with a focus on ordinary themes and narrow perspectives, forming the Hua Jian school of Ci (花间词派, "Flowery school").

Southern Tang had poets like Feng Yansi (冯延巳), Emperors Li Jing (李璟) and Li Yu (李煜, or Li Houzhu 李后主). While they also touched upon courtly life and romantic themes, their Ci were generally more elegant and delicate, marked by artistic innovation. Li Yu, especially after being captured following his kingdom's fall, wrote Ci that conveyed sentiments of longing and nostalgia vividly. These works broke away from the earlier patterns of focusing solely on romantic themes, contributing innovative content and artistic expressions to Song Ci (宋词).

Art

Left: a landscape painting by Li Cheng (919-967). Right: Butterfly and Wisteria Flowers by Xu Xi (886-974).

This period's development of painting continued based on the foundation set by Tang painting, with particular advancements seen in landscape and flower-and-bird painting.

Zen Buddhism flourished during this era, driving the development of mural art. Despite using Tang Dynasty themes, the dominant focus shifted to Mahayana Buddhism's scriptures. The art showed a decline in creativity, with Buddha and Bodhisattva figures appearing rigid and colors monotonous. Portrait paintings, particularly of influential rulers in certain regions, stood out with bold brushwork, vibrant colors, and intricate shading techniques, showcasing a more sophisticated approach to portrait art.