Chinese Dynasty: Enduring Imprint of the Qing Dynasty

The Qing Dynasty, ruling China from 1644 to 1912, was a prosperous and influential period that witnessed significant achievements. Under Manchu leadership, the empire expanded greatly, stretching from the Korean peninsula to Central Asia. Notable accomplishments included the compilation of the vast Siku Quanshu literary collection, preserving Chinese knowledge and culture, as well as advancements in agriculture through new crops and improved farming techniques. The Qing's cultural and technological influence extended beyond China's borders, solidifying its position as a regional and global power.

Political System and Military

Government

The Qing Dynasty's political system largely inherited the Ming's (明朝) monarchial model without a Chancellor (宰相) but established consultative bodies like the Grand Secretariat (内阁) and Grand Council (军机处).

Government positions were split between the Han and Manchus with some given to Mongols. The imperial examination system (科举) was continued to recruit officials. Positions were divided into civil and military roles, with nine ranks each, and each further subdivided into two grades.

Qing officials from late Qianlong period (left) and the late Qing (right)

The emperor held central power directly leading Six Ministries (六部), including Boards of Civil Appointments, Revenue, Rites, War, Punishments, and Works (吏、户、礼、兵、刑、工).

The Grand Secretariat, which had been an important decision-making body during the Ming, lost importance and became an imperial chancery. The Grand Council, established in the 1720s under the Yongzheng Emperor (雍正帝), initially managed military campaigns against the Mongols but later centralized military and administrative authority, acting as the emperor's privy council.

Military

The Qing Dynasty had a unique military and organizational structure named the Eight Banners (八旗), forming the core of its army. Originally integrating military and civilian administration, it later specialized in military affairs. Established by Nurhaci (努尔哈赤) in 1601 with four banners, it expanded to eight by 1615. The system included soldiers and their families, under the jurisdiction of generals or commanders. Despite divisions among Manchu, Mongol, and Han banners, they operated under the same system. Banner people had fixed status, lived separately from civilians, received provisions from the court, and were tried by specific agencies rather than local authorities.

In addition to the Eight Banners, the Qing Dynasty's armed forces included the Green Standard Army (绿营), local militias, volunteer forces, the Xiang Army (湘军), the Huai Army (淮军), and the New Army of the late Qing (清末新军).

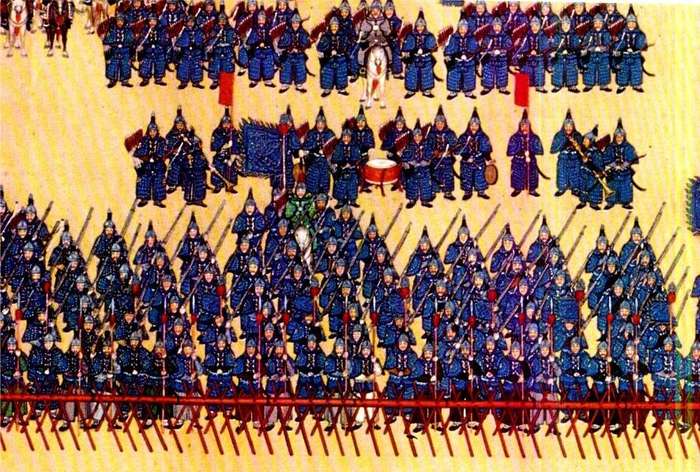

Soldiers of the Blue Banner (one of the Eight Banners) during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor

Economy

During the High Qing era (1683-1799), China's national strength was robust, with significant agricultural, handicraft, and commercial developments. This era marked the pinnacle of economic development in Chinese feudal society, with expanded cultivated land, population growth, and abundant state funds/grain reserves.

In agriculture, policies like reclaiming wasteland, relocating migrants, and promoting new crops boosted production. Economic growth was also driven by increased domestic/foreign trade. Policies rewarded land reclamation, and reduced taxes to mitigate class conflicts.

For handicrafts, the corvée labor system transitioned to tax-substitution labor. Key industries were textiles and ceramics, with cotton surpassing silk. Jingdezhen (景德镇) became the ceramics center, producing enamel-painted porcelain wares.

Commerce

Commerce thrived during the Qing, with market trade being the most prevalent economic activity. Towns and cities were hubs distributing goods and connecting regional markets.

There were two main types of urban markets: town fairs and permanent commercial shops. Urban markets saw growth in fairs and increasing shops, including the emergence of specialized commercial streets. New towns emerged while existing ones expanded business districts.

Urban markets generally served as county-level trading hubs connecting local markets. Some larger ones became regional commodity centers due to scale, production, or transportation links. A few even became inter-provincial trading hubs.

As commerce developed, inter-regional markets took shape like the Qi-Lu (齐鲁, or Shangdong), Zhongyuan (中原), Yan-Bei (燕北, or Beijing-Tianjin) markets in the north and Lingnan (岭南), Jiangnan (江南) markets in the south, each with central trading hub cities.

The Qianlong Emperor's Southern Inspection Tour - Entering Suzhou along the Grand Canal.

The Grand Canal nourished North China's fields and provided governmental revenue through transportation and trade.

A national market emerged, facilitated by unification, a stable society, and unified commercial policies, tax systems, currency, and measurement standards. This was exemplified by the widespread distribution of products from production hubs nationwide. Products like silk from Nanjing (南京) and Guangzhou (广州), Suzhou (苏州) cotton, Foshan (佛山) ironware, Jingdezhen porcelain, Taiwan (台湾) sugar, and Anhui (安徽) and Fujian (福建) tea accessed national markets.

With regional market development, several national central markets took shape, including Beijing, Foshan, Suzhou, Hankou (汉口), and other major hubs.

During this period of growing production, prosperous commerce, and extensive trade routes, a commercial network formed, spanning rural fairs to urban, regional, and national markets.

Concurrently, commercial capital ventured into production. Ten major merchant groups emerged, with the Shanxi (晋商) and Hui merchants (徽商) dominating finance, while Fujian (闽商) and Chaozhou merchants (潮商) controlled overseas trade.

Finance and Monetary

During the High Qing era, the high-interest loan business flourished with the monetary economy's development. Interest rates were commonly 3-5% per month. The Qing court injected lower-interest "bearing silver" funds, expanding capital for high-interest lending.

Specialized lending organizations called Yinju (印局) emerged, charging 3-6% monthly interest. In Jiangnan, Qianzhuang (钱庄, like independent banks) evolved from money-changing to also provide lending and deposit services. In the north, similar Zhangju (账局, "account firms") operated, mostly run by Shanxi merchants lending to businesses, officials, and aristocrats.

Piaohao (票号, "draft banks") emerged, many operated by Shanxi merchants, providing nationwide fund transfer services before modern banking existed. Their rates were around 0.3-0.4% for deposits and 0.7-0.8% for loans.

While still part of the feudal usury capital system, these financial organizations facilitated economic development, long-distance trade, inter-regional exchange, and the emergence of a national market, paving the way for modern banking.

Left: various coins from the Qing Dynasty produced under the Qianlong, Guangxu and Xuantong Emperors.

Right: a Great Qing Treasure Note banknote of 2000 wén issued in 1859.

For currencies, the Qing largely used a bimetallic silver and copper standard, with silver more prominent. Foreign silver coins from European countries circulated widely due to thriving overseas trade.

Before and after the First Opium War, there was a demand for minted, fixed-form silver coins, which only officially began after the war. The Opium War-induced silver outflow from Britain's opium sales created a demand for more copper coins and fueled inflation, severely damaging the economy.

To stabilize the currency, the Qing government issued paper money, which was first issued in 1651 under the Shunzhi Emperor (顺治帝), and again in 1853 with the Xianfeng Emperor's (咸丰帝) Great Qing Treasure Note (大清宝钞) and Ministry of Revenue Government notes (户部官票).

Science and Technology

Overall, scientific and technological development during the Qing lagged behind the West, with the gap widening in the late Qing. Early on, there was active cultural/technical exchange between Qing rulers/scholars and Western missionaries, with new knowledge applied to governance. However, later prohibitions on Christianity led to alienation from Western learning. Despite scientific backwardness contributing to weaknesses, there was notable progress in fields like mathematics and astronomy compared to previous eras.

Astronomy and Geography

After the Qing conquest, Jesuit missionaries brought Western science and technology to China and were appointed to the Imperial Astronomical Bureau and Board of Mathematics (钦天监). They constructed new astronomical instruments and published works improving calendars during the Shunzhi to Qianlong (乾隆) periods. Western physical knowledge spread, influencing Chinese scholars to study optics and prompting research on Western mechanical marvels, aiding experimental physics.

Cartography adopted Western methods like trapezoidal projection, producing world-class maps aided by major mathematical works.

Firearms

To quell the Three Feudatories Revolt (三藩之乱), the Kangxi Emperor (康熙帝) had missionary Ferdinand Verbiest (南怀仁) produce mobile cannons suited for southern China's terrain, introducing Western cannon-making theory and techniques. Over 40 years, nearly 1,000 cannons of various types were cast or modified under imperial supervision.

By 1756, 85 different cannon models were standardized, and works on artillery and firearm operations were published. The Qing military's firearms rate exceeded the Ming's, reaching 50-60% by the Opium Wars with muskets and cast iron/bronze cannons as main armaments.

While the Qing court legally prohibited private gunsmithing, it was difficult to enforce in practice. By the late Qing, civilian firearm production and trade were widespread for self-defense, hunting, and recreation. The Qing permitted the gentry's civil militia forces and civilian hunting/self-defense weapons under certain conditions, though policies wavered.

Battle of Yesil-kol-nor, 1759, showing firearms used by the Qing army in war in the early Qing

Medicine

Progress in medicine and pharmaceuticals largely continued the flourishing developments of the Ming era, such as research into classic texts, herbology, formularies, diagnostics/treatments, and medical case records. However, the most significant achievement was the formulation of a new systemic theory for studying acute infectious diseases.

Early on, missionary physicians like Jean-François Gerbillon (张诚) and Joachim Bouvet (白晋) transmitted Western medical knowledge like anatomy, piquing the Kangxi Emperor's interest. Texts were translated into Manchu, sparking attention from Chinese physicians toward Western theories.

In the mid-late Qing, broader penetration of Western science and technology, including the use of medicine for religious/imperial aims by Western powers, made Western medicine's influence more apparent. This spurred advocacy for an integrated East-West medicine approach. By the late Qing/early Republic period, the influx of advanced Western medicine posed intense competition for traditional Chinese medicine.

Mathematics

Chinese mathematics was highly advanced in ancient times but declined during the Ming. At the end of the Ming, Western mathematics was introduced through translations and works like Euclid's Elements (《几何原本》).

The Qing saw a flourishing of math due to the hiring of European Jesuit missionaries to teach subjects like geometry and astronomy, producing renowned mathematicians like Fang Zhongtong (方中通) and Mei Wending (梅文鼎). But this changed when the Yongzheng Emperor cut off access to Western learning and expelled most missionaries, causing Chinese mathematics to stagnate without new texts.

In the late 18th century under Qianlong, there was a revival of interest in recovering ancient Chinese mathematical works. Qing scholars recovered many long-lost ancient mathematical treatises from sources like the Yongle Encyclopedia (《永乐大典》), and around 500 Qing scholars produced over 1,000 mathematical works, more than any previous dynasty.

Architecture and Infrastructure

Drawing of the Old Summer Palace

Architecture saw great achievements in palaces, gardens, temples, and city walls, with masterful design and decoration. Foreign missionaries introduced Western architectural techniques and designed buildings like the Western-style mansions and waterworks in the Old Summer Palace (圆明园).

Towards the Qing's end, China's transportation developed. Zhan Tianyou (詹天佑), China's first outstanding railway engineer, overcame immense challenges in constructing the Beijing-Zhangjiakou Railway (京张铁路). He innovated with a cost-saving "人-shaped" switchback track design, completing it two years earlier than planned.

Zhan standardized railway specs adopted nationally, like the 4'8.5" gauge. He emphasized training engineers, regulating their evaluations and promotions, and linking salaries to performance ratings. His personnel system became a model for other Chinese railways.

Two trains passing the Qinglongqiao Station on the Beijing-Zhangjiakou Railway

Culture

The Qing thoroughly implemented Sinicization policies while preserving Manchu culture and balancing it with Han culture. Official documents used both Manchu and Chinese scripts. Confucian classics were mandatory for Manchu study as Han culture promoted, though some Confucian ideas were not fully accepted by Qing emperors.

In the 18th century, missionaries' accounts sparked a "Chinoiserie" craze across Europe for around a century, with great enthusiasm for Chinese material, culture, and political system. However, there were also some European critiques of perceived Qing autocracy.

Throughout the Qing, traditional art flourished while innovations occurred across cultural fields. High literacy rates, a thriving publishing industry, and prosperous cities all contributed to a vibrant and creative environment. By the late 19th century, Chinese artistic and cultural circles began grappling with Western and Japanese cosmopolitan influences.

Academics and Thoughts

Scholarship flourished with scholars deeply synthesizing previous academic traditions, an achievement Liang Qichao (梁启超) called the Chinese "Renaissance." Given the corruption and troubles of the late Ming that caused the Neo-Confucian philosophy to become hollow and hypocritical, early Qing scholars turned to pragmatic, policy-oriented studies. They investigated dynastic trajectories and proposed reforms. This gave early Qing thought a pragmatic character, developing an evidence-based, empirical tradition of textual studies.

Kaoju Xue

Kaoju Xue/Kaozheng (考据学, "Evidential Studies"), a Chinese school of thought active during the Qing, emphasized objectivity, empirical verification, and a scientific spirit. It specialized in philology, phonology, and textual criticism, tracing roots to Han Dynasty classicists.

Major figures included Gu Yanwu (顾炎武) advocating "practical studies" over Neo-Confucianism by directly investigating classics, Huang Zongxi (黄宗羲) defending Yangmingism (阳明学) while rejecting Neo-Confucianism thought, and Wang Fuzhi (王夫之) stressing practical action as the basis of knowledge and historical patterns.

In the mid-Qing, Kaoju Xue meticulously verified all aspects of Chinese history. However, Kaoju Xue gradually became overly obsessed with trivial investigations, prompting Zhang Xuecheng (章学诚) to propose that "the Six Classics are all history" (六经皆史), stressing applying their moral principles to contemporary politics to correct this drift. After the Opium War and the influx of Western learning, Kaoju Xue gradually declined.

Western Influence

During the late Ming/early Qing, Jesuit missionaries introduced Western learning to China, shifting academia towards pragmatism. Talented missionaries employed by emperors disseminated advanced Western science and technology. Imperial compilations like Siku Quanshu (《四库全书》) included works by Western missionaries. The Kangxi and Qianlong emperors praised Western studies like measurement, ingenious devices, hydraulic engineering, precise astronomy, and craftsmanship.

After the Opium War, an influx of Western knowledge catalyzed reforms. Scholars like Gong Zizhen (龚自珍), Wei Yuan (魏源), and Kang Youwei (康有为) built on calls to reform ancestral systems. Absorbing Western ideas, they drove movements like the Self-Strengthening Movement (自强运动) and the Hundred Days' Reform (戊戌变法), paving the way for late Qing changes and the 1911 Revolution (辛亥革命).

Literature

Qing Dynasty's literature developed pluralistically, encompassing characteristics from previous eras. The Qing revived declining literary forms from before the Ming, while further advancing novels, operas, and other genres. Interactions between different regions and ethnicities led to a diversification of linguistic styles across poetry, prose, and theatrical works.

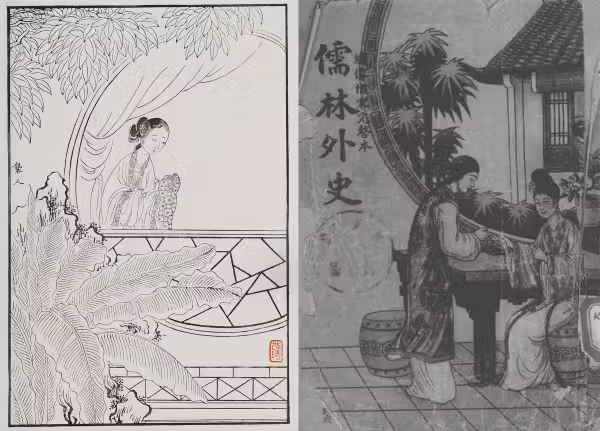

Left: an illustration from the Dream of the Red Chamber.

Right: a 1949 printed edition cover of the The Scholars.

Novels

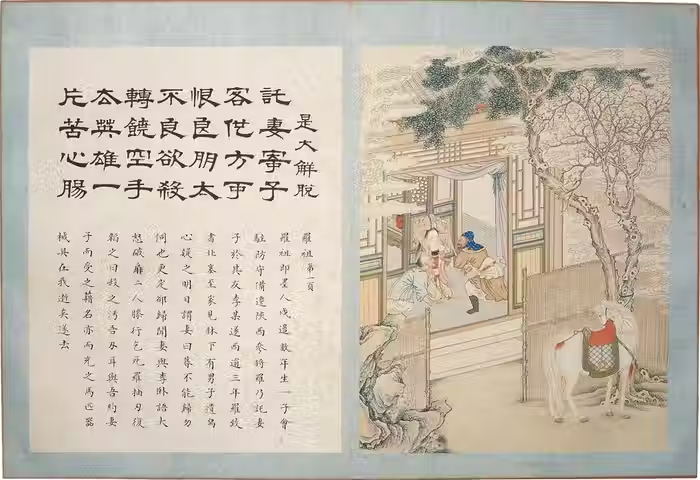

The Qing produced many outstanding novels. Cao Xueqin's (曹雪芹) Dream of the Red Chamber (《红楼梦》) is regarded as the pinnacle of classical Chinese fiction for its comprehensive realist depictions and is one of the Four Classic Chinese Novels (四大名著). Pu Songling's (蒲松龄) Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio (《聊斋志异》) used supernatural tales to reflect society. Wu Jingzi's (吴敬梓) The Scholars (《儒林外史》) is considered a great satirical novel. Condemnatory novels like The Travels of Lao Can (《老残游记》) exposing official ugliness also had a major impact.

A page with illustration from Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio

Poetry

The Qing saw another important period for poetry after the Tang and Song, with numerous schools and diverse ideologies. Early Qing saw the "poetry of the displaced" imbued with resistance, with major figures like Qian Qianyi (钱谦益), Gong Dingzi (龚鼎孳), and Wu Weiye (吴伟业), together known as the Three Masters of Jiangdong (江左三大家). Zhang Wentao (张问陶) during the late Qianlong/early Jiaqing was renowned for exquisite and regulated verses, along with Yuan Mei (袁枚) and Zhao Yi (赵翼), they were collectively known as the Three Masters of the Xingling School (性灵派三大家).

Qing Ci poetry (清词) was considered a "revival," far exceeding previous dynasties in output. By the Kangxi era, Qing Ci established a distinct style alongside Tang and Song traditions. Major poets included Wang Shizhen (王士禛), Zhu Yizun (朱彝尊), and Nalan Xingde (纳兰性德) who guided the creative style, leading Qing Ci to enter its heyday.

Art

Painting

Literati painters were prominent during the Qing, particularly in landscape and ink-wash painting. Artists focused on brushwork and innovative forms, leading to various stylistic schools. Influential artists include Zhu Da (朱耷) and Shi Tao (石涛) in early Qing, the "Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou" (扬州八怪) in mid-Qing, and Ren Bonian (任伯年) and Wu Changshuo (吴昌硕) in late Qing.

Left: Two Birds by Zhu Da. Right: Playing the Flute by Ren Bonian.

Drama

The Qing's regional Chinese operas flourished rapidly. After reforms, the Kunqu opera (昆曲) took center stage.

The term "Jingju" (Beijing/Peking Opera, 京剧) first appeared in 1876. It evolved over decades from the fusion of the four major Hui Opera (徽剧) troupes arriving in Beijing in 1790 with local opera genres like Kunqu and Han opera (汉剧). Jingju became preeminent nationwide in its rich repertoire, number of artists/troupes, audiences, and influence.

Portraits of Peking Opera characters from the late Qing