The Wit and Wisdom of Chinese Two-Part Allegorical Sayings

Among Chinese idiomatic expressions, Xiehouyu (歇后语) stands out as a uniquely clever form that combines wit, wordplay, and wisdom. These two-part allegorical sayings create a verbal puzzle that especially engages listeners - the first part sets up a scene or situation, while the second part delivers meaning through clever wordplay, metaphor, or logical connection. What makes Xiehouyu particularly fascinating is that in actual usage, speakers often only say the first part, leaving listeners to complete the meaning in their minds - hence the name "pause (歇) and continue (后)" expressions (语).

Understanding the Structure and Types

Xiehouyu consists of two distinct parts separated by a dash (——) when written:

1. Setup: The first part presents a scene, situation, or description

2. Punchline: The second part delivers the meaning through various clever devices

There are several main types of Xiehouyu based on how they create meaning:

1. Logical Reasoning

These Xiehouyu rely on cause-and-effect relationships or logical conclusions:

-

哑巴吃黄连 —— 有苦说不出

-

A mute eating bitter herb - cannot express one's bitterness

-

The logical connection between being unable to speak and unable to express suffering

-

-

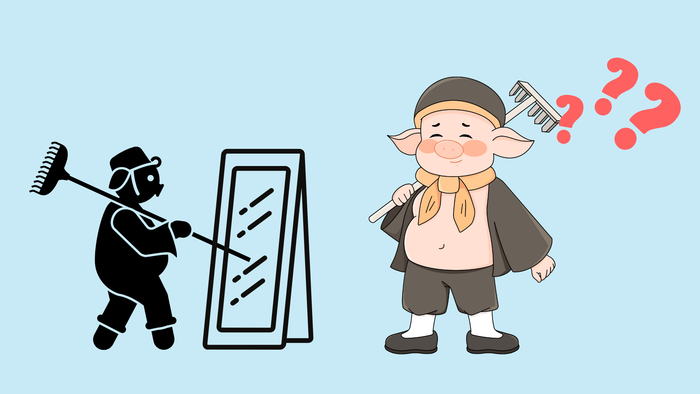

猪八戒照镜子 —— 里外不是人

-

Zhu Bajie looking in the mirror - neither human inside nor out

-

A logical conclusion about one's true nature

-

猪八戒 (Zhu Bajie) is a character from the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West (《西游记》). He was once a heavenly general but was banished to Earth and transformed into a half-man, half-pig creature due to his misdeeds. This expression means "neither human inside nor out," symbolizing someone who doesn't fit in or satisfy anyone.

-

2. Homophonic Wordplay

These expressions use words that sound alike in Chinese for clever effect:

-

孔夫子搬家 —— 净是书(输)

-

Confucius moving house - all books/losses

-

Playing on the homophony between 书 (shū, books) and 输 (shū, to lose)

-

-

百日不下雨 —— 久情(晴)

-

No rain for a hundred days - long-lasting fine weather/affection

-

Using the similar sounds of 情 (qíng, feeling, typically means affection/love) and 晴 (qíng, clear/sunny weather)

-

3. Metaphorical Comparison

These Xiehouyu create meaning through visual or behavioral comparisons:

-

水仙不开花 —— 装蒜

-

Narcissus not blooming - pretending to be a garlic/make a pretense

-

Comparing the closed bulb of narcissus to garlic (蒜)

-

"装蒜" is a slang term in Chinese meaning "make a pretense" or "feigned ignorance"

-

-

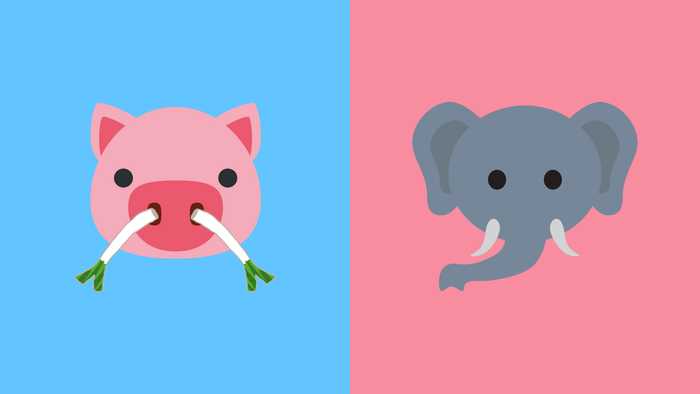

猪鼻孔插葱 —— 装象(相)

-

Leek (green onion) inserted in pig's nose - putting on airs (pretending to be an elephant)

-

Comparing the similar look of a pig with a leek in the nose and an elephant while using wordplay

-

Using the similar sounds of 相 (xiàng, posture, appearance) and 象 (xiàng, elephant)

-

"装相" means pretend, put on an act, or put on airs

-

Cultural Importance of Xiehouyu

Xiehouyu represents a unique aspect of Chinese cultural expression, combining linguistic creativity with social wisdom. These sayings serve multiple cultural functions:

1. Cultural Preservation

-

Captures traditional values and beliefs

-

Preserves historical references and stories

-

Maintains connections to Chinese literary heritage

2. Social Communication

-

Provides indirect ways to express criticism or advice

-

Creates bonds through shared cultural knowledge

-

Adds humor and wit to daily conversation

3. Educational Role

-

Teaches language skills through wordplay

-

Transmits cultural values to younger generations

-

Develops understanding of metaphorical thinking

Thematic Categories

1. Historical References

Many Xiehouyu draw from historical events, figures, or folklore, providing insight into Chinese history and cultural wisdom.

-

关公面前耍大刀 —— 现(献)丑

-

Showing off a big knife in front of Guan Yu – showing one's incompetence

-

Refers to someone embarrassing themselves by trying to show off in front of an expert.

-

关公 is 关羽 (Guan Yu), who was a legendary general known for his martial prowess and loyalty in the Three Kingdoms period.

-

-

刘备借荆州 —— 只借不还

-

Liu Bei borrows Jingzhou – only borrows, never returns

-

Describes someone who takes advantage of others' generosity without reciprocation.

-

刘备 (Liu Bei) was a key figure and ruler during the Three Kingdoms period. He borrowed Jingzhou strategically but did not return it, symbolizing taking advantage of someone's generosity.

-

-

姜太公钓鱼 —— 愿者上钩

-

Jiang Ziya fishing – the willing take the bait

-

Refers to people willingly falling into a situation or trap.

-

姜太公 or 姜子牙 (Jiang Ziya) was a famous strategist whose method of fishing (without bait) symbolized waiting for the willing.

-

-

韩信点兵 —— 多多益善

-

Han Xin organizing soldiers – the more, the better

-

Implies that abundance, especially of resources, is advantageous.

-

韩信 (Han Xin) was a brilliant military general. The phrase, "the more, the better," reflects his belief that having more soldiers strengthened his strategy.

-

-

曹操用计 —— 又尖又滑

-

Cao Cao using a strategy – sharp and slippery

-

Describes someone as cunning or sly, often employing crafty tactics.

-

曹操 (Cao Cao) was a military leader known for his cunning and ruthlessness during the Three Kingdoms.

-

2. Daily Life Observations

Many Xiehouyu often reflect everyday experiences and observations, often with humorous twists.

-

纸糊的琵琶 —— 免弹(谈)

-

A pipa made of paper – no point in playing/discussion

-

Used to describe something that's not worth discussing or unusable.

-

Pipa (琵琶) is a traditional Chinese musical instrument.

-

Using the similar sound of 弹 (tán, play (an instrument)) and 谈 (tán, discussion)

-

-

打开天窗 —— 说亮话

-

Opening a skylight – speaking openly

-

Means being frank or transparent in a conversation.

-

亮 usually means bright, but "亮话" means speaking frankly/straightforward

-

-

白开水画画 —— 清(轻)描淡写

-

Drawing with plain water – lightly sketching

-

Describes an understated or casual approach.

-

Using the similar sound of 清 (qīng, clear (water)) and 轻 (qīng, lightly)

-

-

热锅上的蚂蚁 —— 团团转

-

An ant on a hot pan – spinning in circles

-

Describes someone in a frantic or agitated state.

-

3. Social Commentary

Many Xiehouyu provide insight or critique of human behavior, relationships, and social dynamics.

-

狗咬吕洞宾 —— 不识好人心

-

A dog biting Lü Dongbin – unable to recognize kindness

-

Refers to someone ungrateful or unable to recognize good intentions.

-

吕洞宾 (Lü Dongbin) is a famous Daoist immortal and one of the Eight Immortals in Chinese mythology, often seen as a benevolent figure.

-

-

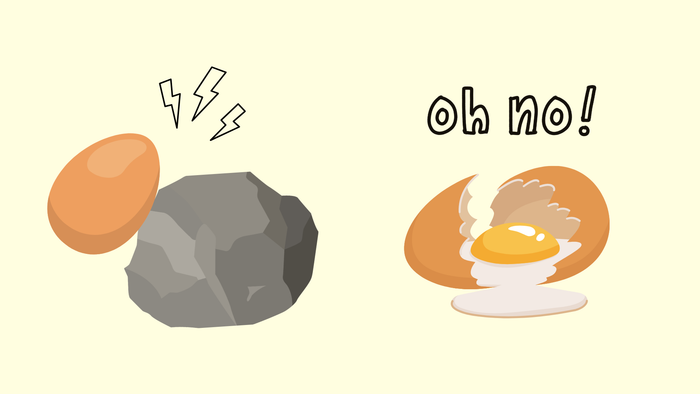

鸡蛋碰石头 —— 不自量力

-

An egg striking a stone – overestimating one's strength

-

Criticizes overly confident or reckless behavior.

-

-

肉包子打狗 —— 有去无回

-

Throwing a meat bun at a dog – gone and never coming back

-

Used when something is given or sent with no expectation of it returning.

-

4. Animal-Related

Many Xiehouyu use animal behaviors and characteristics as metaphors to comment on human actions and social situations.

-

兔子尾巴 —— 长不了

-

A rabbit's tail – won't grow long

-

Implies that something is unsustainable or won't last long.

-

-

猫哭耗子 —— 假慈悲

-

A cat crying over a mouse – fake compassion

-

Criticizes hypocritical or insincere displays of concern.

-

-

黄鼠狼给鸡拜年 —— 没安好心

-

A weasel wishing a chicken Happy New Year – no good intentions

-

Refers to someone with hidden motives or ill intentions.

-

-

癞蛤蟆想吃天鹅肉 —— 痴心妄想

-

A toad wanting to eat swan meat – delusional dreams

-

Refers to unrealistic or impossible desires.

-

5. Mythology/Fairy-Tale Related

Drawing from Chinese mythology and folklore, these Xiehouyu bring legendary figures and mythical beings into daily expressions, adding cultural depth and humor.

-

龙王跳海 —— 回老家

-

The Dragon King jumps into the sea – returning home

-

Describes someone returning to their origins or where they belong.

-

In Chinese mythology, 龙王 (Long Wang), or the Dragon King, is the god of the sea and ruler of underwater realms.

-

-

孙悟空大闹天宫 —— 慌了神

-

Sun Wukong causing havoc in Heaven – leaving everyone flustered

-

Describes a chaotic situation that leaves people in a panic.

-

孙悟空 (Sun Wukong), main character from Journey to the West, is a powerful Monkey King known for his rebellious nature and magical powers. The phrase "大闹天宫" (causing havoc in Heaven) describes his legendary uproar against the heavens, which left the gods in disarray.

-

"慌了神" is a pun, meaning both "to panic" (慌神) and "startling (慌) the gods (神)".

-

-

财神爷吹牛 —— 有的是钱

-

The God of Wealth boasting – has plenty of money

-

Refers to someone flaunting their resources or wealth.

-

"吹牛" (chuī niú) is a colloquial term meaning "to boast" or "to brag."

-

-

八仙过海 —— 各显神通

-

The Eight Immortals crossing the sea – each displaying their powers

-

Everyone uses their unique skills to tackle a challenge.

-

The 八仙 (Eight Immortals) are popular figures in Chinese folklore, each possessing unique magical abilities.

-

How Xiehouyu Lives in Conversation

Imagine a lively tea shop in China, where friends gather for tea and laughter. When describing an ungrateful person, one might say, "狗咬吕洞宾" (a dog biting Lü Dongbin), and everyone instantly recalls the unspoken ending, "不识好人心" (unable to recognize kindness). The phrase resonates with the group, turning a serious observation into a moment of shared humor.

Xiehouyu naturally weaves itself into conversations, adding layers of meaning and humor. In the workplace, a team racing against a deadline might find someone quip, "热锅上的蚂蚁" (an ant on a hot pan), hinting at the unspoken "团团转" (spinning in circles) to capture the team's frenzied energy. This shared knowledge softens the stress with a laugh.

During family gatherings, Xiehouyu serves as both wisdom and amusement. When discussing a friend's unrealistic goals, an elder might say, "癞蛤蟆想吃天鹅肉" (a toad wanting to eat swan meat), and everyone completes the phrase in their minds, chuckling at the implication of "痴心妄想" (delusional dreams). Such phrases provide a gentle critique wrapped in humor.

This blend of humor, insight, and shared understanding makes Xiehouyu more than just an expression—it's a connection, a way to turn observations into moments of mutual appreciation.

Modern Life and Evolution

Though rooted in tradition, Xiehouyu remains a vibrant part of contemporary Chinese culture. These expressions bring humor and wisdom to daily life, making them popular in modern settings. Young people, for instance, often use Xiehouyu in social media posts, adding a witty touch to comments on everyday situations.

In today's China, Xiehouyu appears in various contexts while maintaining its role as a source of entertainment and wisdom:

-

In casual social media posts, where friends use them to make witty comments about daily life

-

In comedy shows and entertainment programs, where their clever wordplay adds layers of humor

-

In workplace banter, where they help maintain a light atmosphere while making points indirectly

Even in professional settings, Xiehouyu can lighten the mood or indirectly make a point. For example, if a colleague's efforts are proving ineffective, someone might say "纸糊的琵琶——免谈" (a pipa made of paper - not worth playing), suggesting in a humorous way that a project or idea may lack substance.

The endurance of Xiehouyu in modern Chinese society shows how traditional wit remains relevant in contemporary life. By combining clever imagery, wordplay, and cultural wisdom with a dash of humor, they continue to entertain while serving as a bridge between China's rich cultural heritage and modern communication needs.

A Legacy of Wit and Wisdom

Xiehouyu represents a unique intersection of linguistic creativity, cultural wisdom, and social commentary in the Chinese language. Its enduring popularity demonstrates how traditional forms of expression can maintain relevance while preserving cultural values. Through its clever combination of setup and punchline, Xiehouyu continues to offer insights into the Chinese language and culture, making it an invaluable part of China's linguistic heritage.

Understanding and appreciating Xiehouyu not only helps learners master Chinese language skills but also provides deep insights into Chinese ways of thinking and communication. As we continue to value and preserve these expressions, they serve as bridges between past and present, helping maintain the richness and depth of Chinese cultural communication.